Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

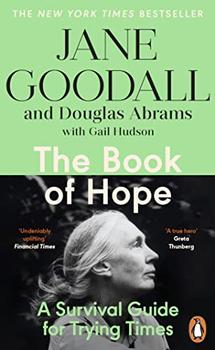

A Survival Guide for Trying Times (Global Icons Series)

by Jane Goodall, Douglas Abrams

For her, an evening tot of whisky is a nightly ritual and an opportunity to relax and, when possible, toast with friends.

"It all started," she explained, "because Mum and I always shared a 'wee dram' every evening when I was at home. So we went on raising a glass to each other at 7 p.m. wherever I was in the world." She has also found that when her voice gets really tired from too many interviews and lectures, a small sip of whisky tightens the vocal cords and enables her to get through a lecture. "And," said Jane, "four opera singers and one popular rock singer have told me that this works for them, too."

I sat next to Jane at the outdoor table on the veranda as she and her family laughed and told stories. The thick bougainvillea surrounding us almost felt like a forest canopy in the candlelight. Merlin, her eldest grandson, was twenty-five years old. Years earlier, when he was eighteen, after a wild night with friends he had dived into an empty swimming pool. He was left with a broken neck, and the injury had caused him to change his life, to give up partying, and, like his sister Angel, follow his grandmother into conservation work. Jane, the understated matriarch, sat at the head of the table, her pride clearly evident.

Jane put mosquito repellent on her ankles and we joked that the mosquitos were not vegetarians. "Only the female sucks blood," Jane pointed out. "The males just live off nectar." Through the eyes of the naturalist, the bloodsucking mosquitoes were simply mothers who were trying to get a blood meal to feed their offspring. That didn't quite change my dislike of these historic foes of humanity, however.

As the conversation and family stories paused, I wanted to ask Jane the questions that had been absorbing me ever since we first decided to collaborate on a book about hope.

As a born-and-raised and somewhat skeptical New Yorker, I had to admit that I was suspicious of hope. It seemed like a weak response, a passive acceptance—"let's hope for the best." It seemed like a panacea or a fantasy. A willful denial or blind faith to cling to despite the facts and the grim reality of life. I was afraid of having false hope, that misguided imposter. Even cynicism felt safer in some ways than taking the risk of hope. Certainly, fear and anger seemed like more useful responses, ready to sound the alarm, especially during times of crisis like this.

I also wanted to know what the difference was between hope and optimism, whether Jane had ever lost hope, and how we keep hope in dark times. But these questions would need to wait until the next morning, as it was getting late and the dinner party was breaking up.

Is Hope Real?

When I returned the next day—a little less nervous—to begin our conversation about hope, Jane and I sat on her veranda in old, sturdy wooden folding chairs with green canvas seats and backs. We looked out at the backyard so filled with trees that it was almost impossible to see the Indian Ocean just beyond. A chorus of tropical birds sang, screeched, cackled, and called. Two rescue dogs came to curl up at Jane's feet, and a cat meowed through a screen, insistent about contributing to the conversation. Jane seemed a little like a modern-day Saint Francis of Assisi, surrounded by and protecting all the animals.

"What is hope?" I began. "How do you define it?"

"Hope," Jane said, "is what enables us to keep going in the face of adversity. It is what we desire to happen, but we must be prepared to work hard to make it so." Jane grinned. "Like hoping this will be a good book. But it won't be if we don't bloody work at it."

I smiled. "Yes, that is definitely one of my hopes, too. You said that hope is what we desire to happen, but we need to be prepared to work hard. So does hope require action?"

"I don't think all hope requires action, because sometimes you can't take action. If you're in a cell in a prison where you've been thrown for no good reason, you can't take action, but you can still hope to get out. I've been communicating with a group of conservationists who have been tried and given long sentences for putting up camera traps to record the presence of wildlife. They're living in hope for the day they're released through the actions of others, but they can't actually take action themselves."

Excerpted from The Book of Hope by Jane Goodall and Douglas Abrams. Copyright © 2021 by Jane Goodall and Douglas Abrams. Excerpted by permission of Celadon. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.