Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

He's gone, that boy, along with his sisters, wee things that came to the market only when the mother was there, trailing behind like ducklings, with the same odd waddle of a walk that only winged creatures have. Perhaps this is why they weren't for this earth for very long. The girls five and two, the boy all of eleven in that New Year. She sent the boy, alone sometimes, to run errands for the fam-ily, sometimes let me have him run errands so he could make a little of his own money on the side, a few gouds to call his own, to make him feel grown, or growing. I knew him well, as did my clients for whom I had him run errands, especially up at the hotel on the mountain, perched above the city. He was quick, quick, and mostly reliable. He reminded me of my own son, Richard, at that

age, except that I had a presentiment that unlike mine, he would grow up to be a fine man. I had been wrong concerning them both. My son grew to be a wealthy, respected man, though I no longer knew him by then. Jonas would never become the man I could see hovering already in the shadows of his eyes and vanishing smiles.

The girls were crushed beneath a house over there, not far from the market. Playing in the streets. Darting in and out of the houses, nothing unusual. I watched them do this daily from my seat low to the ground. Watched the boy count his steps from his stoop to the market, then to my stall, backward, forward, as if he could solve a mystery with his calculations—so much like his father, the accountant with hardly a cent to his name, but rich in other ways: his family, for one. Anyone could see that he had married the love of his life, ran to her like a man runs to water in a desert. No wonder it would be fire we would have to save her from, in the end, months after the disaster. The boy had left my stall with his one egg for his mother in hand, then gone down the street and into a house with a television on, turned out to face the street so that everyone could gather inside and outside to watch the futbòl games or, that day, a soap opera. The woman who owned the house was a childless woman, a widow or a divorcée. She, too, would not survive.

When the earth moved, the houses fell to the ground within seconds, jolted when the ground stopped swaying and crushed everything that had remained. The girls were not the only ones left crying below: the whole street swayed; the earth rippled like a carpet heaving itself of crumbs and dirt that a distracted house-keeper had forgotten to sweep away. I left my stand and all my wares—the piles of mango, the eggs (they would fall, smash against the ground), the packs of Chiclets, the ripe avocadoes—and made my way toward the voices, not thinking of my own small house up and away in the hills. I was not worried for my own: Anne, my granddaughter, had left for her work, far away in another country, after her mother's funeral, and Richard, her father, my son, well, we had stopped worrying for him long ago, carrying with us solely the memory of him as the small child we had raised, before he left us, leaving behind, carelessly, a stray seed for us to water. We buried our grief in the process, watching Anne grow. Our son, the man, we did not know.

I watched. That's what old market women do: we watch. But this time, the lot of us market women sprang to action, even as our bones creaked for lack of cartilage and oil. Like the others on the street, we used anything in hand we could find. Useless things like spoons and forks, the metal ends of umbrellas, as if our puny things, our fingernails, could move all that. Only the lucky were saved. Be-ing lucky meant simply that you were closer to the surface, or that fewer things blocked the way to being found. We heard people on their cell phones, all up and down the street, begging frantically for help, giving directions to where they thought they were beneath the rubble, within the rooms of their houses. Phones rang and we heard people answer them. Then—fewer and fewer voices. The tinny, per-sistent ringing of cell phone tones: different songs rising like wind from underground with no answer.

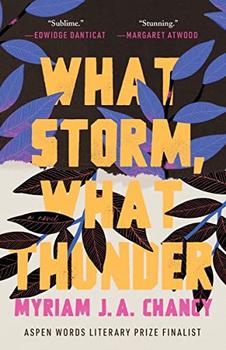

Excerpted from What Storm, What Thunder by Myriam J Chancy . Copyright © 2021 by Myriam J Chancy . Excerpted by permission of Tin House Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.