Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

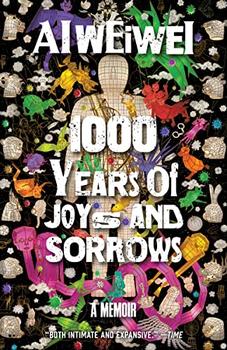

A Memoir

by Ai WeiweiChapter One

Pellucid Night

Boisterous laughter erupts along the path

A bunch of boozers stumble out of the sleeping village

Clatter their way toward the sleeping fields

On this night, this pellucid night

I was born in 1957, eight years after the founding of the "New China." My father was forty-seven. When I was growing up, my father rarely talked about the past, because everything was shrouded in the thick fog of the dominant political narrative, and any inquiry into fact ran the risk of provoking a backlash too awful to contemplate. In satisfying the demands of the new order, the Chinese people suffered a withering of spiritual life and lost the ability to tell things as they had truly occurred.

It was half a century before I began to reflect on this. On April 3, 2011, as I was about to fly out of Beijing's Capital Airport, a swarm of plainclothes police descended on me, and for the next eighty-one days I disappeared into a black hole. During my confinement I began to reflect on the past: I thought of my father, in particular, and tried to imagine what life had been like for him behind the bars of a Nationalist prison eighty years earlier. I realized I knew very little about his ordeal, and I had never taken an active interest in his experiences. In the era in which I grew up, ideological indoctrination exposed us to an intense, invasive light that made our memories vanish like shadows. Memories were a burden, and it was best to be done with them; soon people lost not only the will but the power to remember. When yesterday, today, and tomorrow merge into an indistinguishable blur, memory—apart from being potentially dangerous—has very little meaning at all.

Many of my earliest memories are fractured. When I was a young boy, the world to me was a split screen. On one side, U.S. imperialists strutted around in tuxedos and top hats, walking sticks in hand, trailed by their running dogs: the British, French, Germans, Italians, and Japanese, along with the Kuomintang reactionaries entrenched on Taiwan. On the other side stood Mao Zedong and the sunflowers flanking him—that's to say: the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, seeking independence and liberation from colonialism and imperialism; it was we who represented the light and the future. In propaganda pictures, the Vietnamese leader, "Grandpa" Ho Chi Minh, was accompanied by fearless young Vietnamese in bamboo hats, their guns trained on the U.S. warplanes in the sky above. Every day we were treated to heroic stories of their victories over the Yankee bandits. An unbridgeable gulf existed between the two sides.

In that information-deprived era, personal choice was like floating duckweed, rootless and insubstantial. Denied the nourishment of individual interests and attachments, memory, wrung out to dry, ruptured and crumbled: "The proletariat has to liberate all of humanity before it can liberate itself," the saying went. After all the convulsions that China had experienced, genuine emotions and personal memory were reduced to tiny scraps and easily replaced by the discourse of struggle and continuous revolution.

The good thing is that my father was a writer. In poetry he recorded feelings that had lodged deep in his heart, even if those little streams of honesty and candor had no natural outlet on those many occasions when political floods carried all before them. Today, all I can do is pick up the scattered fragments left after the storm and try to piece together a picture, however incomplete it may be.

The year I was born, Mao Zedong unleashed a political storm—the Anti-Rightist Campaign, designed to purge "rightist" intellectuals who had criticized the government. The whirlpool that swallowed up my father upended my life too, leaving a mark on me that I carry to this day. As a leading "rightist" among Chinese writers, my father was exiled and forced to undergo "reform through labor," bringing to an abrupt end the relatively comfortable life that he had enjoyed after the establishment of the new regime in 1949. Expelled at first to the icy wilderness of the far northeast, we were later transferred to the town of Shihezi, at the foot of Xinjiang's Tian Shan mountain range. Like a little boat finding refuge in a typhoon, we sheltered there until the political winds shifted direction again.

Excerpted from 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows by Ai Weiwei. Copyright © 2021 by Ai Weiwei. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Talent hits a target no one else can hit; Genius hits a target no one else can see.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.