Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

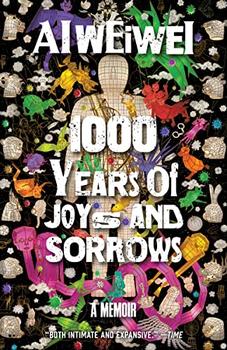

A Memoir

by Ai Weiwei

Then, in 1967, Mao's "Cultural Revolution" entered a new stage, and my father, now seen as a purveyor of bourgeois literature and art, was once again placed on the blacklist of ideological targets, along with other Trotskyists, apostates, and anti-party elements. I was about to turn ten, and the events that followed have stayed with me always.

In May of that year, one of the leading revolutionary radicals in Shihezi visited us in our home. My father had been living too cushy a life, he said, and now they were going to send him to a remote paramilitary production unit for "remolding."

Father offered no response.

"Are you looking to us to give you a farewell party?" the man sneered.

Not long after that, a "Liberation" truck pulled up outside the front door of our house. We loaded it with a few simple items of furniture and a pile of coal, and tossed our bedrolls on top—we didn't have much else to take. It began to drizzle as Father took a seat in the front cabin; my stepbrother, Gao Jian, and I clambered onto the back of the truck and squatted under the canvas. The place we were going was on the edge of the Gurbantünggüt Desert; it was known locally as "Little Siberia."

Rather than go with us, my mother decided to take my little brother, Ai Dan, back to Beijing. After ten years in exile, she was no longer young, and she couldn't stomach the prospect of living in even more primitive conditions. Shihezi was the farthest she was willing to go. There was no way to keep the family together. I did not beg Mother to go with us, nor did I plead with her to leave my little brother behind. I held my tongue, neither saying goodbye nor asking if she was coming back. I don't remember how long it took for them to disappear from view as we drove off. As far as I was concerned, staying was no different from leaving: either way, it was not our decision to make.

The truck shook violently as it lurched along a seemingly endless dirt road riven with potholes and gullies, and I had to hold tight to the frame to avoid being tossed in the air. A mat beside us was picked up by a gust of wind and within seconds it swirled away, disappearing into the cloud of dust thrown up in our wake.

After several bone-shaking hours, the truck finally ground to a halt at the edge of the desert. We had arrived at our destination: Xinjiang Military District Production and Construction Corps, Agricultural Division 8, Regiment 23, Branch 3, Company 2. It was one of many such units established in China's border regions in the 1950s, with two goals in mind. In times of peace, Production and Construction Corps workers would develop land for cultivation and engage in agricultural production, boosting the nation's economy. If war broke out with one of China's neighbors, or if there was unrest among the ethnic minority population, the workers would take up their military role and assist in national defense efforts. As we were to learn firsthand, such units sometimes had an additional function—the housing of offenders banished from their native homes elsewhere in China.

It was dusk, and the sound of a flute came wafting over from a row of low-standing cottages; several young workers were standing outside, watching us curiously. We were assigned a room that had a double bed but nothing else. My father and I moved in the small table and four stools that we had brought from Shihezi. The floor was tamped earth and the walls were mud brick with wheat stalks sticking out. I made a simple oil lamp by pouring kerosene into an empty medicine bottle, poking a hole in the bottle cap, and threading a scrap of shoelace through it.

My father required little in life apart from time to read and write. And he had few responsibilities. It was my mother who had always handled the housework, and she had never expected us to lend a hand. But now it was just my father, Gao Jian, and me, and our living arrangements aroused the curiosity of the other workers, rough-and-ready "military farm warriors" who were blunt in their inquiries. "Is that your grandpa?" they would ask me, or "Do you miss your mom?" In time I learned how to look after things myself.

Excerpted from 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows by Ai Weiwei. Copyright © 2021 by Ai Weiwei. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

It is among the commonplaces of education that we often first cut off the living root and then try to replace its ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.