Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The diner here is famous for its 1950s memorabilia. She sits at the counter and orders the lumberjack special. She pictures a lumberjack laying her across his lap, breaking her, like a twig, in half. She eats a sausage link and one of three sunny-side-up eggs, a bit of the pancake just for the mouthful of syrup. This diner, with its defunct Coke machines and jukeboxes and old graphic lunchboxes, reminds her of her mother's house, crammed with dangerous nostalgia. A woman and her toddler sit nearby. She spoons cereal into his wet little mouth. He dribbles and she wipes. He dribbles and she wipes. Easy as that. The woman is wearing all linen and a large-brimmed hat; she looks old to be a mother. But who is she to say who is old and who is not? She was thirty-five when she got pregnant, thirty-six when she lost her child. And now she feels one hundred, or maybe only seven years old. She looks a moment too long. Something passes between them, the mother and her, a warm current of it: pity, or maybe its cousin, contempt. When she asks for the bill the man at the counter, pointing to the table where the mother and son were sitting, says, They said to say good luck.

In the bathroom mirror, she lets herself look up. She sees what the woman must have seen: the gaunt face, the hair matted to one side, the lips chapped, the nails bitten to the quick. She splashes cold water on her face and pulls her hair back. She looks nearly dead. This is not that. She looks down at her clothes; they are dirty but intact.

It is hot. The hottest day yet. August, slinking into September. Still hot by the evening, when the sun is a red face dipping its chin into the water. The public beach is empty. Everyone is on their patios sipping Campari and eating pistachios, saying their farewells. She removes her canvas shoes, her jeans and shirt, and moves into the water – sharp and cold as a knife's edge. She swims out until, when she turns her head, she can no longer make out her clothes bundled up on the sand, just a single line of darkness in the background. The water is bitter now, the moon just a sliver in the night, barely any comfort at all. She is that sliver, she thinks, drowning in the dark. She could die here, so slight and sinking. Nothing but her body to buoy her up. Whatever reserves she had, she has lost them now. She feels a rush of heat around her, her own urine, terror at her own thoughts. She thrashes around, trying to turn back, but even this turning, this changing course, seems impossible: the body has forgotten how to lead. It takes an eternity to move against the current, the arms and legs dumb with disuse and then too much exertion. She kicks hard, and then softer, it is easier this way, without trying at all; she is moving forward and back, lulled by the waves. She is like this forever, until she hits something, a rock, and then her knees hit it too, and she finds that she can crawl. Beneath her, the hard, wet certainty of the ground. She manages to get to her feet, finds her clothes in their pile, falls asleep in a damp heap.

She wakes before the sun and sits up, stiff and cold. She has always wanted this: to slip beneath the surface, to dispossess herself. Now that she has done it, it is hard to remember how her self could have become such a bottomless pit: feed me, fuck me, fill me, love me.

This is what it feels like to slip, she remembers telling her husband, when she was teaching him to ice skate on the Ottawa canal. You can't teach someone how to slip. He was right: you slip and then you've slipped and so you know.

Sometimes, she pictures them: her brother and his wife, discussing her now that she is gone. Impossible, that's what they would say. Or maybe, instead, beyond repair.

The management has moved her things. You were gone for two nights, they tell her. She can only remember one, but she doesn't want to fight. Her things include: a toothbrush, a sweater, two T-shirts, one pair of jeans, the biography of a famous chef, all stuffed inside an old backpack with her brother's initials embroidered on it: p.s.t. They have placed her in the large dormitory. She can tell from the work boots neatly lining the beds that the place is full of men. She buys a six-pack of beer and some cigarettes and brings them with her to the beach. She will wait until the men are sleeping before climbing back into her cot. She lies down. The beer and cigarettes are effective; she feels herself drifting pleasantly into the night. Today she has only eaten half a packet of tea cookies and a banana. The waves are loud, brimming over, coursing to their violent meter. Before she falls asleep, she thinks: This is what babies must hear when they are held inside the womb.

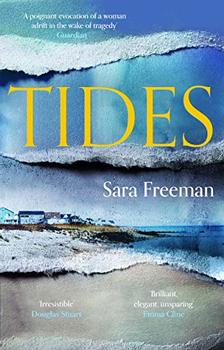

Excerpted from Tides by Sara Freeman. Copyright © 2022 by Sara Freeman. Excerpted by permission of Grove Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

If we did all the things we are capable of, we would literally astound ourselves

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.