Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

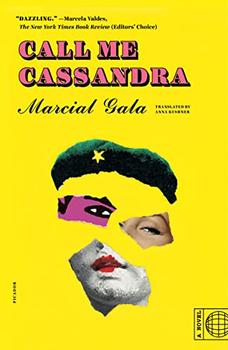

A Novel

by Marcial Gala

"Yes," I say, taking the captain's member in my mouth, and then spitting out what he deposits there. I stand up and look out the window, from which the sea is not visible, just the red, hot soil of Angola.

"Why are you up so early?" my mother says behind me. "You're not tired anymore?"

"No, I'm not tired anymore."

But what I can see are the bullets tearing through me, and how I fall so far away from her and from my father, who went out and still hasn't come back. I know where my father is: with the Russian lady, that English teacher we met on the beach at Rancho Luna the day that my mother couldn't come with us because she had a cold, and then my father took us in the old Chevy, and as soon as we got our swimsuits on, my brother and I ran into the warm water, screaming happily, and when we came out, my father was sitting on the sand, talking to a tall blond woman who made a strange contrast to him, because she was refined and had well-manicured hands, while my father's hands are always filthy. He introduced her to us and it turned out the woman was Russian and her name was Lyudmila.

"Like that Gurchenko woman," my father specified.

That Russian woman was very strange, she had almond-shaped eyes, very large, and of a blue so dark they looked black. She gave a kiss to each of us on our wet faces and asked my brother and me what grade we were in and whether we liked to read.

"I want a snack," was my brother's response.

"Fifth grade," I said. "And yes, I like to read."

"Fifth grade?" The Russian woman was surprised. "You seem younger."

"Yeah, he's kind of a midget," my father said and let out a laugh. "He takes after me, but you don't measure a man from his head to the skies, but rather from the skies to his head."

"What about a woman?" the Russian asked, in her pink bikini so tiny that every man walking along the beach turned his head to get a better look, and my father's eyes were so wide it looked like he could fit the whole world inside.

"I want a snack," my brother insisted, and my father, who was naked from the waist up to show off his former-gymnast's muscles, took his wallet from his jeans pocket and held out five pesos to my brother and me.

"Go over to the lunch counter and get whatever you want. Take care of Rauli," he said to my brother, who was already fourteen, which made him think he was a man, and when we're sitting at the lunch counter, he tells me that Russian woman is a whore and that our father is a motherfucker. He says it without bitterness, just like someone repeating a fact. We eat croquettes and have a yogurt, and when we get back to the shore, the tall woman and Papá are still talking, so my brother gives him the change and we head back to the water. I dive in. My Zeus, when I'm at the bottom, I open my eyes and see a fish coming up to me and looking at me and I dream that I am that fish and a boy named Raúl is looking at me, and I feel affected by the transmutation of things and beings, although I don't know that word, I'm just a ten-year-old kid who went to the beach and who finally comes up for air from the deep and sees his father talking to a woman he doesn't know.

"Don't go tattling on me to your mother. Be men," my father says when we get into the Chevy. "If you tell her, I won't bring you to the beach anymore."

"No need to threaten us," my brother says. "Twenty pesos and I won't say a word."

"You think you can blackmail me, you piece of trash?" my father says, but then smiles and hands him the twenty pesos. "You're learning too much."

If I close my eyes, I see him taking the Russian woman to bed and doing something with her body that my ten-year-old self doesn't really understand, but I don't tell my mother because I know she won't like it and she has problems enough already without having to hear about my father and Lyudmila, who later shows up on a very hot day with a plate of potatoes with butter, saying it was a recipe of her grandmother's from Ukraine, and there are smiles all around and she pats my head and looks at José from afar, as if she were scared of him. My brother has a bad rap, the Russian woman respects my brother, my father has whispered to her that he's a difficult kid who's about to get sent to reform school. She likes me better. I know how the Russian woman will die, of a myocardial infarction following a raging case of diabetes, in 2011, just shy of seventy years old, in a suburban neighborhood of Volgograd, formerly Stalingrad. At ten, I can see the Russian woman's death, can see how she opens her mouth asking for water that Sergei, her teenage grandson, doesn't bring her. The Russian woman, in addition to the boiled potatoes with butter, brings something for José and something for me, a Pushkin book that she places in my mother's hand like some kind of great treasure. One thing's for sure: she gets my mother to smile when she flips through the book, because it's in Russian.

Copyright © 2019 by Marcial Gala

Translation copyright © 2022 by Anna Kushner

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.