Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

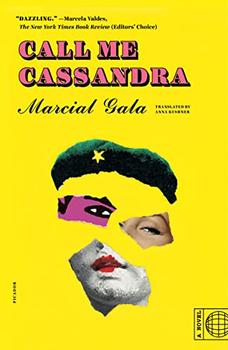

A Novel

by Marcial Gala

"They're not going to understand a word, Svetlana," she tells her, although she is well aware that the Russian woman's name is Lyudmila.

That's how my mother is—there's no one better at fucking with people.

My mother works as the secretary for a boss who makes her feel important, at least more important than my father, a mere auto body repairman, who almost always gets back late to the apartment, tipsy and in overalls so covered in grease and gasoline that she has to go to great lengths to leave them spotless. My father says not to wash them on his account, to just leave them like that, but my mother spends her Sunday mornings soaping and brushing those rough-hewn work clothes.

Atop the living room console are my father's medals from when he was a gymnast, and a picture of him up on the podium of a young socialist athletes' competition.

At lunchtime, the four of us sit at the big dining room table and my mother insists we use all the silverware, but the spoon is all my father needs.

"You're no example for your children," my mother tells him.

"No, I'm not," he admits. "I'm an animal, not like that boss of yours, the mulato."

My father hates Ricardo, my mother's boss, who sometimes shows up at the house with a bottle of vodka as a gift of appreciation for his secretary's immense dedication. My mother's eyes well up as she takes the bottle, which she never even tastes. My father drinks the bottle without even thanking her. She's so naïve that she lets herself be introduced to the Russian woman without it even occurring to her that this woman, as refined and distinguished as if she sprang from the pages of a European magazine, would ever notice a brute like my father.

My father is called José Raúl Iriarte Gómez and he was born in Placetas, a small town full of bitter provincial types of Spanish origins who hate themselves for having stayed in town and envy all those who left. My grandfather was called José Ignacio and was a farmworker and an unabashed cockfighter. My grandmother Carmen spoke Galician and grew cabbage and lettuce that she sold all over Placetas. Besides my father, she had four other children, naming each one José, and they all, with the exception of my father, died violently. The oldest two joined the rebel army. José Eduardo was nabbed by a squad of rural guards, en route to the Sierra Maestra, and machine-gunned down on the side of the road. José Roberto was slaughtered in Santa Clara when they took over the armored train. The other two were killed by the same husband who found José Ricardo, the youngest, sleeping with his wife, while the other one, José Felipe, was leaning up against the back wall of the house, playing the guitar, singing a ranchera and keeping watch. He couldn't have been a very good lookout, since he didn't hear the approach of the man whom everyone in Placetas knew as Juan the Party Crusher.

"The knife went through José Felipe's kidney," the doctor told my grandmother. "If not for that, he would have survived."

José Ricardo's jugular was slashed by the jealous man, who then stabbed his wife so many times that, according to what my father says when he's drunk and missing his brothers, the guy had a fit and nearly died when he saw the woman he'd killed, so soaked in blood it would turn your stomach. Sometimes my grandparents had nothing to eat but some cornmeal with salt and a little bit of tomato sauce if tomatoes were in season. After the Triumph of the Revolution, my father, who was a teenager by then, focused on sports and mechanics, bought a Chevy from one of those petit bourgeois from Punta Gorda who emigrated as soon as they found out lovely little Cuba was plunging headfirst into communism.

My mother is called Mariela Fonseca Linares and she was born in Cruces, which wasn't yet the grimy town it ended up becoming, but rather a small, prosperous city, with several newspapers and radio stations and an allegedly active cultural life. My mother's mother, Elena Elisa Linares Argüelles, married a white-passing mulato named Eduardo Fonseca Escobar, a card-carrying member of the Socialist Party and an attorney, a graduate of one of those colleges in the U.S. South that is just for Blacks. My grandmother's family, sugar plantation owners known throughout the province of Las Villas as the Linares, never forgave her that inappropriate love and disinherited her, so my grandmother became a schoolteacher and, with her husband, built a little wooden house that still stands in Cruces. They had twin daughters. My aunt Nancy came out very blond and with blue eyes like me, while my mother was so olive-skinned that at school they called her the Gypsy. They were very close, and when my mother moved to Cienfuegos, her sister moved, too, and lived with us until she got sick with cancer and died. I was eleven years old when Nancy died and my mother was never the same again. Neither was I.

Copyright © 2019 by Marcial Gala

Translation copyright © 2022 by Anna Kushner

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.