Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

There is something about a pool which – not to make too gross a pun on it – encourages the reflective, leads the mind not merely to transcribe the experience of the actual, to give it a topography, but allows the questions of why it means what it does, what its reality consists of, to what extent everything that confronts you is more than the local.

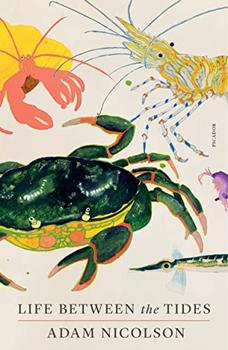

There are no boundaries here. The human, the planetary and the animal all interact, and all of them are inter-leaved in the realities of the shore. None makes sense without the others. The billions of acres of galactic time and the varying gravitational fields through which this planet swings count for as much as the daily actions of people and all the behaviours of the creatures in the intertidal. These categories blur: human life here, even human thought here, is identifiably animal; animals develop social and cognitive systems, means of attack and defence, hierarchy and cooperation, propagation and survival, that look strikingly like the ways human beings organise their lives and societies. Clans of prawns live in the pools; winkles can smell out their enemies; the pools are governed by the movement of the planets; philosophical understandings can be applied to the ecology of invertebrates; the life of the crabs is attuned to the tides.

This is not anthropomorphism – viewing the animal world according to terms more suitable to people – but its opposite: zoomorphism, recognising the continuities between animal and human consciousness, the continuousness of the spectrum that runs from bacterium and virus to scientist and poet. All can exist only within the overarching embrace of the world-as-it-is, each life driven by the need to be, each unaware of the significance of what it is that drives them. That unknowability is everywhere here and is part of what I mean to say: to know something, a person or an animal or a place, to become intimate with it, is not to know in any very conscious way but to dissolve the boundaries. To be with anything, life must overflow its brim. 'We stand, then, on the shore,' William Golding wrote in 1965, reviewing Gavin Maxwell's Ring of Bright Water,

not as our Victorian fathers stood, lassoing phenomena with Latin names, listing, docketing and systematising … We pore [instead] over the natural language of nature, the limy wormcasts in a shell, 'strange hieroglyphics that even in their simplest form may appear urgently significant, the symbols of some forgotten alphabet …' We walk among the layers of disintegrating coral, along the straggling line of 'brown sea-wrack, dizzy with jumping sandhoppers'. We stand among the flotsam, the odd shoes and tins, hot-water bottles and skulls of sheep or deer. We know nothing. We look daily at the mystery of plain stuff. We stand where any upright food-gatherer has stood, on the edge of our own unconscious.

The first Greek philosophers experienced the world as what they called physis, a term that is famously difficult to translate but is somewhere close to the idea of 'growing'. Nature for them was something in the act of becoming, what Martin Heidegger, entranced by these early thinkers, called an 'upsurging presence', a 'process of arising', a 'self-blossoming emergence', a gift from nothing, the coming into being of being itself. That net of miraculous beginnings, in all dimensions, is what this book is about.

Excerpted from Life Between the Tides by Adam Nicolson. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by Adam Nicolson. All rights reserved.

A library is a temple unabridged with priceless treasure...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.