Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

In point of fact, Asia was born on a Thursday.

Edwin, Rosalie's little brother, is four. Edwin is crying, which he does the way he does all things, quietly. He's been trying to collect pebbles and seed pods to be passengers in his boats, but Asia keeps taking them and throwing them into the spring.

Rosalie comes to kneel beside him, pushes up her sleeve with one hand and reaches into the cold water with the other. She's distracted momentarily by the magic of her fingers elongating and refracting. Asia cannot throw well; Edwin's pebbles are easily rescued. She hands three back to him, wiping her cold hand on the hem of her skirt.

This makes Asia so angry she can't even speak. She points to the water and sobs. She stamps her feet and screams. Mother comes to the door again. "We're all fine here," Rosalie says, but she speaks so softly that only Asia and Edwin hear her. What she says makes Asia even louder and angrier since it isn't at all true.

All two-year-olds have terrible tempers, Mother says, but the others didn't, not like this. In the face of Asia's fury, Edwin surrenders his boats and his pebbles; Asia has them all now. Her cheeks dry in an instant. Already she has the beauty Rosalie lacks, dark hair, dark, shining eyes.

So does Edwin, who comes to lean against Rosalie, his bony shoulder cutting sharply into her upper arm. He smells like the biscuits they had at breakfast. Mrs. Elijah Rogers, their neighbor, had to teach Mother to make biscuits and cornbread on the kitchen's hearth when she first arrived at the farm. Now she's teaching Rosalie. A childless woman herself, she dotes on the Booths, all of whom call her Aunty. "I don't think your mother had ever cooked before," Aunty Rogers once told Rosalie, either to let her know that Mother was a real lady or else that Mother had been strangely incompetent by Bel Air standards; Rosalie has never been sure which was being conveyed.

Mother's biscuits are fine now, but not as good as Aunty Rogers'. Or, to be honest, Rosalie's.

"The frog is sleeping," Edwin says. This doesn't sound like a question, but is. He wants to be told he is right. Edwin only asks questions when he already knows the answers.

"Old Mr. Bullfrog sleeps through the winter," Rosalie says. "He only wakes up when summer comes."

"Old Mr. Bullfrog is very old." Edwin is feeding her her lines. "Very very old."

"A hundred years."

Bullfrogs don't live a hundred years; they are lucky to make eight. Grandfather says so. And yet Rosalie cannot remember a summer out of earshot of the enormous, bulbous frog. On warm evenings, when the insects are humming and the birds calling and the water rushing and the wind blowing and the trees rustling and the cows bawling, still that deep, booming groan can be heard. Neighbors a mile distant complain of the noise.

"At least a hundred years. He saw the American Revolution with his very own eyes. He drank the tea in the Boston harbor." Rosalie feels her voice strangling in her throat. Henry Byron had always been the author of Old Mr. Bullfrog's rich and consequential past.

Some neighbors once approached Father with a request that the frog be killed in the cause of peace and quiet. Father refused. The farm is a sanctuary for all God's creatures, even the copperhead snakes. Father doesn't believe in eating meat and once, Mother says, rose up in a saloon to point his finger at a man enjoying a plate of oysters. "Murderer! Murderer! Murderer!" Father said in the same voice he used to play Macbeth. Sometimes you think Father might be joking, but you never can be sure.

Asia has finished throwing all of Edwin's boats and stones into the water. She turns in his direction a face shining with triumph, but immediately clouds over with the realization that Edwin hasn't been watching. She steps towards them and Rosalie shifts Edwin to her other side so he can't be pushed about. His knees soften until he's sitting in her lap. Asia comes to do the same, crowding into Rosalie's arms, taking up as much room as she can. Heat pours off her. Rosalie feels Edwin becoming smaller.

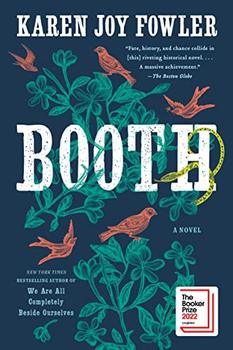

Excerpted from Booth by Karen Joy Fowler. Copyright © 2022 by Karen Joy Fowler. Excerpted by permission of G.P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.