Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

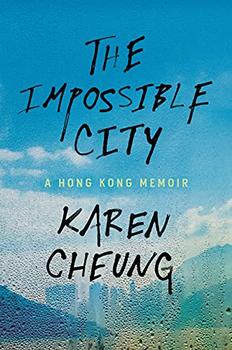

A Hong Kong Memoir

by Karen CheungExcerpt

The Impossible City

1997

Summers in Hong Kong always heave with rain, but on this first of July, the downpour feels deliberate, overdone. The water is charging down the steps, drenching our concrete pavements, dripping from the banyan trees. The observatory hoists the black rainstorm signal, to warn us of tumbling landslides. It is too neat a metaphor, but still we're pointing to the sky, mumbling to ourselves: It's crying.

I am four years old. After my parents' separation, my mother and little brother move to Singapore. They live in a property overlooking the East Coast beach, where I would later spend my summers rollerblading and sitting on the back of my mother's bike. They won't return, and neither will my father and I move there as he had promised. I'd grow up as if I were a single child. But I don't know that, not yet. My grandmother is seventy, and her post-retirement project is me. When I'm running a fever late in the middle of the night, she places a damp cloth over my head, takes me to the doctor first thing in the morning, so you don't get brain damage, she says. When I fall over, she buries a silver ring inside the yolk of a boiled egg, wraps a cloth around it, then rubs it over my bruises to help blood circulation.

Our days are quiet, uneventful. I attend a kindergarten near my family's tong lau home in To Kwa Wan, humming along to "Descendants of the Dragon" with the rest of my class, its Chinese nationalist sentiments lost on me: In the Ancient East there is a dragon, / her name is China / In the Ancient East there is a people, / they are all the heirs of the dragon. While I'm at school, my grandmother goes to the wet market at a municipal building with a red apple painted on its façade. The market stinks of chicken feathers and animal carcasses. She puts on the Cantonese opera song《鳳閣恩仇未了情》 and makes soy sauce chicken wings, steamed pork cakes, clear broths that have been boiling away all day: dinner for me and her four aging children. Then we make the trip back to Villa Athena in Ma On Shan, a ten-tower upscale housing estate on a road lined with trees and overlooking the Tolo Harbour, where we live with my father.

My father drives us home in his silver BMW, a new car that mirrors the swagger of the young businessman he is then, the child of Chinese immigrants who came to Hong Kong with nothing. Above us, a slice of moon is impaled upon the dark trees, away from the city lights and skyscrapers. I fall asleep on the leathery seats I would later associate with the scent of money, or I am singing along to the Teresa Teng songs my father plays on the stereo system. Teresa Teng is the Taiwanese goddess of song. "If I hadn't met you, where would I be now?" she sings over the speakers in《我只在乎你》.

My father can't speak Mandarin properly even after decades of working in China, even after marrying a Chinese woman, but he knows the words to all of Teresa's songs. Her voice coos from our cassette players, on the radio in a cab, at the local grocer's in Hong Kong. Beijing called her songs "spiritual pollution" and banned her music in the 1980s, but despite this, people throughout Hong Kong, China, and Taiwan are smitten by her, united not in politics but at least by a love for Teresa Teng.

We crawl through the Tate's Cairn Tunnel's beige interior as the line of lights above us makes ghostly imprints on the windshield. For the few minutes it takes to cross, my heart races. I'm always scared that we'll be trapped there forever, that we won't emerge, or that the world will look different when we're finally at the other end.

Across Hong Kong, an anxious mood has punctured the smog. Near my grandmother's flat is the old Kai Tak Airport, which would be decommissioned in a year's time. We can see airplanes from my grandmother's window, taking Hong Kongers far away from here, to Canada, to the United States, to Australia. Every takeoff sends tremors that make the windows shiver, long piercing whistles like a kettle going off. They're leaving for a new life somewhere before the handover, before Communist China takes hold of the city. I'm oblivious to it all. My grandmother takes me to the waterfront park, where I play with grasshoppers and on slides. We have banana splits at the clubhouse at our apartment block, which is guarded by a statue of the goddess Athena herself. Gran buckles me onto the stallion on the merry-go-round inside the Ma On Shan mall, and her gaze follows me as I go up and down and around, become one with the constellation of bright lights.

Excerpted from The Impossible City by Karen Cheung. Copyright © 2022 by Karen Cheung. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.