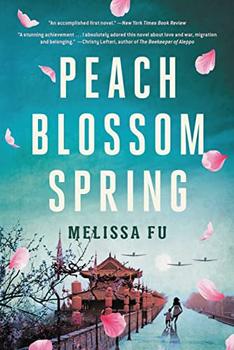

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Melissa FuOrigins

Tell us, they say, tell us where you're from.

He is from walking and walking and walking. He is from shoes filled with holes, blistered toes and calloused heels that know the roughness of gravel roads and the relief in straw, in grass. He is from staying each night in a different place, sometimes city, sometimes country. From roads that wrap around mountains and dip through valleys. From waterways shrouded in fog and mist.

He is from walking across China.

Tell us your memories, they say.

He remembers kerosene lamps burning low, the smell of woodsmoke, cold stone floors under his bare feet. Urgent voices, the rasping of coins, carts creaking at night. He remembers a sandalwood puzzle picture. One way up, there were one hundred monkeys. Turn it over, there were ninety-nine. How did that monkey appear and disappear? He is from this mystery.

Tell us more, they say as they nestle by his side. How did you come here?

He crossed rivers. He crossed oceans.

He carried a watch bought from a sailor, a letter to open doors. A suitcase, a packet of light blue aerogrammes, a single pair of wool socks.

He went towards the call of a beautiful country, a beckoning dream, a promise made of air. Towards wingbeats of birds, kaleidoscopes of seasons he'd never imagined before.

And now, they say, their eyes clear and voices playful, tell us a story.

To know a story is to stroke the silken surfaces of loss, to feel the weight of beauty in his hands.

To know a story is to carry it always, etched in his bones, even if dormant for decades.

Tell us, they insist.

To tell a story, he realises, is to plant a seed and let it grow.

Chapter 1

Changsha, Hunan Province, China, March 1938

Dao Hongtse had three wives. Their names are not important.

The first wife had the first son, Dao Zhiwen. This boy was too wild. He grabbed his first-son privileges with one hand and cast away his first-son duties with the other. He changed his name to Longwei and swaggered out of the house and into the streets. He gambled and won, then gambled and lost. Longwei loves tobacco, whiskey and women.

The first wife had two more children: a girl who grew into a sallow, thin woman whom no one wanted to marry, and a son who died at five months. With a heart bound by grief and feet bound by the old traditions, the first wife is now little more than a wraith lost in folds of opium smoke. She only ventures out of her chamber to refill her pipe and condemn the rest of the household.

Hongtse's second wife works hard. Her back is broad and her hands are rough. She lives in fear of the shrieks and howls of first wife. Hongtse doesn't love her, but he depends on her. Yet the second wife bore only daughters. Their names are not important. They married young and produced sons for other families.

His third wife was the favourite. Hongtse even loved her. She will be forever beautiful because she died in childbirth, bringing Hongtse his youngest son, Dao Xiaowen.

Dao Hongtse's business, Heavenly Light Kerosene and Antiques, has been passed down from father to son for generations. Kerosene is a good business: everyone needs heat, everyone needs light. Hongtse's customers are Nationalists, Communists, merchants, peasants, farmers. One day, Longwei will inherit the business and its responsibilities.

Up a narrow staircase, in a room above the kerosene shop, Dao Hongtse also trades gold coins, jade, antique carvings and hand scrolls. Easy to move, hard to trace, always valuable. He has trained Xiaowen in the art of discerning between that which is of lasting value and that which is of momentary delight.

Between his eldest and his youngest sons, Hongtse covers all possibilities. Where Longwei is street-smart, Xiaowen is book-wise. If Longwei offers bluster, Xiaowen articulates with a fine brush. What Longwei settles by force, Xiaowen negotiates. As the years pass, Longwei has only daughters, but Xiaowen has a son.

Excerpted from Peach Blossom Spring by Melissa Fu. Copyright © 2022 by Melissa Fu. Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.