Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment, and the Courts to Set Him Free

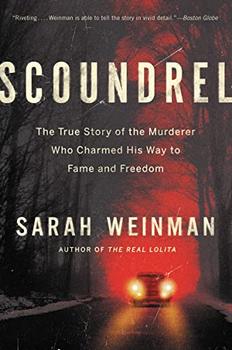

by Sarah Weinman

By the end of 1971, the tide had turned fully in Smith's favor. A federal court of appeals threw out his confession and ordered a new trial. After a seesaw battle between state and federal powers, Smith walked out of court a free man. Officially, he had pleaded guilty to second-degree murder, and he was credited with nearly fifteen years of time served. Immediately after the guilty plea and the final ruling, Smith climbed into a limousine, Buckley took the seat next to him, and they went straight to the television studio to record two riveting hours of Firing Line, which aired on consecutive weeks.

Edgar Smith became a go-to guy on all things prison related. He published book reviews in Playboy and a self-interview in Esquire, appeared on The Mike Douglas Show and many radio programs, and returned home to Bergen County, ignoring and at times openly mocking the cloud of suspicion emanating from his neighbors. He published a thriller, 71 Hours, under the pseudonym Michael Mason and then another book of nonfiction under his own name, Getting Out. He met and married a much younger woman who believed in his innocence and moved with her to California. Then his celebrity status dissipated, and the gigs dried up. His wife became the breadwinner.

In October 1976, an old pattern asserted itself. Having been turned down for a job at the San Diego Union-Tribune, Smith lay in wait in a supermarket parking lot, where he dragged thirty-three-year-old Lefteriya Lisa Ozbun into his car and, while driving with one hand, attempted to stab her to death with the other. He came close to committing his second murder, but Ozbun struggled mightily, kicked a hole in the windshield, and managed to pull the car over, alerting a nearby motorist. Spooked, Smith fled in the damaged car, dumped it for another, and spent the next two weeks as a fugitive, tapping his family for help and money. When those sources dried up, he called Buckley's office, reaching his secretary. She learned that Smith was in Las Vegas under an assumed name. She told Buckley, who promptly called the FBI and turned Smith in.

The following year at trial, Smith confessed to killing Victoria Zielinski: "I recognized that the devil I had been looking at for the last forty-three years was me," he told the court. "It was at that time I recognized that my life had reached a point at which I had a choice of doing two things: I could kill myself or I could return to San Diego and face what I was." He received a life sentence for the attempted murder of Lisa Ozbun and spent the rest of his days behind bars. He died at the California Medical Facility in Vacaville, California, seven years before he was next eligible for parole, in 2024, by which time he would have turned ninety.

* * *

HUMANS ARE HARDWIRED to believe what other humans tell them. Most people merit that belief and, when they breach it, try to atone for their mistakes. Then there are those humans who are able to manipulate, obfuscate, and make a mockery of well-meaning people, causing harm that takes years, if ever, to fully overcome. Writing Scoundrel was a way for me to comprehend what can seem like the incomprehensible: how Edgar Smith was able to fool so many who entered his orbit, be they intimates or strangers, and bend the American criminal justice system to his will. What I came to realize is that this story is a forgotten part of American history at the nexus of justice, prison reform, civil rights, neoconservatism, and literary culture.

William F. Buckley's attempt to free Edgar Smith resulted in catastrophic collateral damage to women: Smith's victims. Edgar had already robbed Victoria Zielinski of her chance to grow up before Buckley became involved with him. Lisa Ozbun came close to death, surviving only through happenstance and her own tenacious will to live. Smith's wives and many of his paramours and female friends suffered psychological damage that lasted the rest of their lives.

Excerpted from Scoundrel by Sarah Weinman. Copyright © 2022 by Sarah Weinman. Excerpted by permission of Ecco. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

If passion drives you, let reason hold the reins

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.