Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

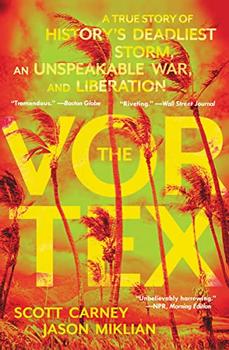

A True Story of History's Deadliest Storm, an Unspeakable War, and Liberation

by Scott Carney , Jason MiklianPrologue

Blackout

BAY OF BENGAL

NOVEMBER 11, 1970

Twenty-four hours before landfall

White mist surged across the Mahajagmitra's bridge and the ship's aging frame creaked with each menacing gust. The man in charge, Captain Nesari, watched the pressure fall a bit more on his ship's barometer and paced the length of the control room. With its holds crammed to capacity with jute fiber and steel, the ship rocked ominously as it inched toward the open sea.

Nesari and his ship were leaving the great Hooghly River, the westernmost finger of India's Ganges delta and one of the world's most troublesome waterways. The Hooghly meets the Bay of Bengal at a point about thirty miles south of Calcutta, where incalculable volumes of silt wash down from the Himalayas and form a fan of ever-shifting rivers, tributaries, and temporary islands. A freighter that alights on a sandbar here might never break free.

As if to prove the point, the rusty hulls of abandoned vessels dotted the seascape. Colossal silt deposits alter the map on an almost daily basis, which is why Nesari hired the expert river pilot R. K. Das from the Port of Calcutta to navigate this stretch of water. Das deftly guided the six-thousand-ton ship through the narrow channels as the wind began to pick up.

Nesari darted his eyes back and forth between the barometer and a stack of outdated maps as he tried to estimate the coming storm's strength. The stakes were high. Waiting out the weather system would add at least a day to their two-week trip to Oman. It would mean that the company would have to pay another day's worth of salaries to the crew of forty-eight seamen, deplete another day's worth of fuel, and stretch their already narrow profit margins to the breaking point—all potentially fireable offenses for any captain who signed off on such a cost overrun.

Then again, pushing onward out of the delta would expose the ship to the full power of whatever weather system lay just over the horizon. The worst-case scenario was too terrifying to contemplate. So Nesari had a decision to make: Would he take the risk, or would he power down?

If it was just a squall, then the Mahajagmitra would be fine. But what if they were witnessing the edge of a cyclone? Cyclonic storms—called hurricanes in the Americas and typhoons in the Pacific Rim—are especially deadly in the Bay of Bengal. Here storms spin counterclockwise, which means that any ship leaving the Port of Calcutta would have to travel directly into the center of the storm's power—facing potentially devastating wind and waves head-on. Once a ship turned southward, the wind would crash against the port side, which could capsize a vulnerable vessel.

Nesari thought of his family and then considered his first mate. David Machado wore the starched white uniform of the Indian Merchant Navy, complete with three gold stripes and a diamond on his epaulettes. Machado couldn't help cracking into a smile when he thought no one was looking. Last week, he'd married the love of his life. After the ceremony in South India, the newlyweds flew to Calcutta together. Sailors like him didn't always get to pick the location of their honeymoon, yet somehow he'd convinced his bride that a cruise to the Middle East would be a fine way to start their life together.

Machado's wife stowed herself below deck, her heavy wedding jewelry tucked safely away in a trunk in their shared compartment. The crew knew the ancient Greek warning that women on board were bad luck. Ostensibly, this was because women caused distractions, but more superstitious sailors claimed that they also attracted misfortune and bad weather. Captain Nesari was glad that they lived in more civilized times.

It was November 11, 1970, yet despite thousands of years of seafaring, a sailor's ability to predict the weather hadn't improved much since the nineteenth century. The radio was the biggest breakthrough in the last hundred years and allowed mariners to speak with other ships who were closer to dangerous weather systems. A smart navigator could triangulate a storm's center by matching other ships' weather reports to his ship's current position—a method that wasn't so different from how truckers relayed traffic patterns to their colleagues over CB radios.

Excerpted from The Vortex by Scott Carney and Jason Miklian. Copyright © 2022 by Scott Carney and Jason Miklian. Excerpted by permission of Ecco. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The dirtiest book of all is the expurgated book

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.