Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Excerpt

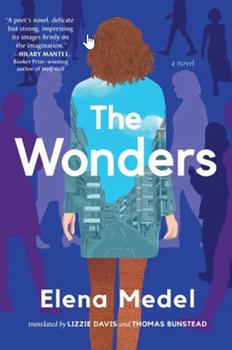

The Wonders

She checked her pockets and found nothing. Her pant pockets, then the ones in her jacket: not so much as a used tissue. In her purse, nothing but a euro and a twenty-centimo coin. Alicia won't need any money till after her shift ends, but it makes her uncomfortable, this feeling of being so close to zero. I work at the train station, in a convenience store, the one near the public restrooms: that's how she usually introduces herself. There are no ATMs without fees in Atocha, so she gets off the metro one stop early and looks for a branch of her bank, withdrawing twenty euros to ease her mind. With this solitary note in her pocket, Alicia looks out at the virtually deserted traffic circle, a few cars, a few pedestrians. Shortly, the sky will start growing light. Given the choice, Alicia always takes the late shift: that way she gets to wake up when she likes, spend the afternoon at the shop, then go directly home. Nando grumbles when that happens, or all the time, really, while she claims it's better for her coworker, who has two kids, so the early shift suits her. But it means having the first few hours of the day to herself, and avoiding evenings at the bar with his friends—who are hers, too, by default—cheap tapas, babies, dirty napkins everywhere. Alicia always thought the ritual would end when the others became parents, but they just wait till the kids start to doze and come straight back once they're in a deep sleep, and it upsets Nando when she tries to get out of it. At least give me that, he says. That sometimes means spending the whole second half of the day in the bar downstairs, and other times, traveling with him on that season's cycling tour: he rides his bike, she goes along in a car with the other women. Alicia considers the word esposa, meaning both "spouse" and "handcuff," and how the sound of the word and its meaning never seem more precisely linked than on those weekends: the skin on her wrists stings, as if chafed by metal. At night, in the hostel—cheap, coarse sheets—Nando bites his lip and clamps a hand over her mouth so the noise doesn't give them away, and after he's finished, asks why she always tries to avoid these trips when they do her so much good.

And so it goes on, day after night, and night after day, sometimes melding into one another, day night night day, and a morning never comes when she calls in sick and just walks through the city instead, and there's never a night without the same recurring nightmare. Her supervisors— she's had several, always men with shirts tucked in, at first a little older than her, these days a little younger—applaud her for staying on so long, years and years in the same post. Some of them ask if she doesn't get bored taking money for travel kits all day long, and she tells them, no, she's happy; for her, it's enough. They appreciate that in particular: it's reassuring to hear she's happy, the convenience-store girl—Patricia, wasn't that your name? One of them wanted to know if she didn't have dreams: if you only knew, she thought—the man with the limp flashing through her thoughts, his dead body swinging in circles—while in her boss's mind she was picturing luxury urban apartments, months lounging on beaches with crystalline waters.

Early shift or late, she approaches it the same: if she works the early, she always picks Nando up afterward or waits for him to call, or they have drinks in the bar to the soundtrack of other people's kids crying; if the late, she finds more satisfying ways to spend her time. Some mornings, she puts on a little makeup, though she doesn't know what to accentuate these days—over time, fat has come to settle on her hips and thighs, and there are the rat eyes she inherited from her mother, who inherited them from her father, or so her Uncle Chico claims in a tone of lament—and she walks through neighborhoods Nando never sets foot in, feigns interest over coffee in a bar where they haven't yet managed to hire a chef, across from a butcher shop that's closing down.

From The Wonders by Elena Medel, translated by Lizzie Davis and Thomas Bunstead. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. Copyright © 2022 by Elena Medel. All rights reserved.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.