Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

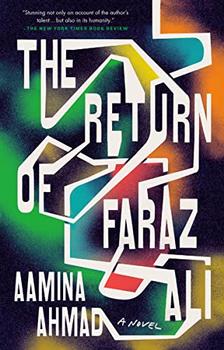

by Aamina AhmadOne

Lahore, 8th November 1968

Faraz stared into the fog, sensing the movement of men, their animals. As the mist shifted and stretched, he glimpsed only fragments: the horns of a bull, the eyes of shawled men on a street corner, the blue flicker of gas cookers. But he heard everything. The whine of the wooden carts, the strike of a match, the snuffling of beasts.

He wasn't sure where he and his men were. They had been led by the officers from Anarkali Police Station through winding streets and now they were somewhere near Mochi Gate, one of the twelve doorways to the walled city, but that was all he knew. The sound of the riot was distant, like the static of radio. The street vendors who'd lingered longer than they should have were nervous now; they dropped their wares as they packed up their things, clipped their animals and their apprentices about the ears, berating them for being too slow. He sensed the nerves of his officers, too, as they lined up next to him. He was jittery himself. This wasn't their beat; he and his men were just reinforcements driven in from Ichra, a place known only for its bazaar crammed with cheap goods, far from the elegance of Mall Road, from Lahore's gardens and the walled city's alleys.

"Closer," he said to the men on either side of him, and so they pressed in, their shoulders touching his. They could not afford to get separated or lost. He felt the men lined up behind him pushing. They were panting; the air, the city, was panting. Or perhaps it was him, perhaps he was panting. He couldn't see much so he tried to still himself to hear better. The troublemakers couldn't be far; they had gathered just outside Mochi Gate to wait for Bhutto, who was just as impatient for battle with President Ayub as they were, who was, they said, bringing a revolution with him. They didn't know police orders were to stop Bhutto from getting to Lahore, but it didn't matter. Bhutto or no Bhutto, everyone knew there would be trouble. The gardens could only be a few hundred yards away but just now he couldn't hear them, couldn't hear anything anymore. Closer, he thought, and his men pressed in again, though he had not spoken out loud. He was still listening when a minute later, or perhaps just seconds later, a dog trotted out of the fog. It looked around, tongue hanging out in the cool air. It took a few steps one way, then the other, skittish, sensing danger. Thick black letters had been painted on the dog's brown fur: ayub, they spelled. The officer next to Faraz gasped, incredulous at this smear on the president's good name. A rifle somewhere in the line was cocked, an officer poised to shoot, to obliterate this insult, but before that could happen, the air cleared and there they finally were: the rioters.

He squinted. They were boys-just boys. They waved their arms, they chanted; he saw their mouths, their white teeth in the dim light. They took a step toward the lines of armed police but then stopped, uncertain. Faraz waited, willed the boys to disappear back into the fog. But a moment later the ground shook. The boys barreled toward him, his men. And because he was surprised, he was late with the order to charge, and later he would wonder if he actually said it at all. Someone said it, or he did, or no one did, but their bodies knew what to do, or did what they had to, and they charged; a roar, and he was inside it.

When he brought down the lathi the first time, he hit air, then the ground. The second time he heard a crack. Maybe a shoulder, a skull; bone. The clink of a tear gas can as it rolled on the ground. A hiss. The smoke caught in his throat, his nostrils, his eyes stung with it. He brought down his lathi again and again. His eyes were closed but streaming, the only sound his breath. When he paused, he realized he was exhausted, as if he had been doing this forever. The line of officers was gone. His men were scattered, some tearing after the boys, others scrambling from them. Plumes of white smoke hung in the air. The street emptied, the noise of the riot became a hum somewhere else-everything slowed-and the thought flickered, like an unexpected memory: What is this for again?

Excerpted from The Return of Faraz Ali by Aamina Ahmad. Copyright © 2022 by Aamina Ahmad. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.