Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

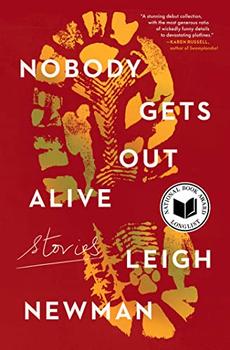

Stories

by Leigh Newman

"The sleepy kind," I said. "Enough for a seventy-pound—well—female."

She looked out the window, as if the world beyond the glass was just one vast, sparkling diorama. "I think it's going to be fine, flying through the pass," she said. "What do you think?"

What I thought was that Rodge didn't put in enough flight hours, but had a great touch with short landings. The odds of him smashing his Cub into the side of a mountain were the same as anybody's: a matter of skill, luck, and weather.

It wasn't as if her concerns were that far-fetched. Flying in the wilderness, all your everyday, ordinary b.s.—being tired, being lazy, trusting the clouds instead of your instruments, losing your prescription sunglasses, forgetting to check your fuel lines—can kill you. And if it doesn't, a door can still blow off your plane and hit the tail or your kid can run between a brownie and her cub or your husband can slip on wet, frozen shale and fall a few thousand feet down a mountain, lose the pack and sat phone, break a leg, and that is that. Which is something you've got to live with, chandeliers or no chandeliers.

"I made him a checklist," she said as I rummaged through the bottles at the bottom of her purse. "Mixture. Prop. Master switch. Fuel pump. Throttle."

By the time she got to cowl flaps, I had long stopped listening. One of the biggest shames about Candace is that she still has a pilot's license. Her not flying, she said, started with kids, strapping them into their little car seats in the back and realizing there was nothing—nothing—underneath them.

Sometimes I wish I had known her before that idea took hold.

"Play me a song, Candace," I said. "It'll make you feel better."

"You know what Rodge doesn't like?" she said.

"Natives," I said, because he doesn't. He got held up for a "travel tax" by one random Athabascan—on Athabascan land—and now he is one of those cocktail-party racists who like to pretend to talk politics just so they can slip in how the Natives and the Park Service have taken over the state. He and I nod to each other at meetings for the homeowners association and leave it at that.

"Anal sex," she said, her voice as light as chickweed pollen. "He won't even try it."

"Look," I said, holding up a pill bottle. "How many of these things did you take?"

"I could live without him," she said. "I know how to waitress. I could get the kids and me one of those cute little houses off O'Malley."

I had some idea of what she was doing, only because I had done it myself, which was leaving her husband in her mind, in case he did die out in the Brooks Range—which he wasn't going to—so that, hopefully, she'd fall apart a little less. But the thing about having gotten divorced four times and widowed once is that people forget you also got married each time. You and your soft, secret, pink balloon of dreams.

"If you want anal sex, Candace," I said, "just drive yourself down to Las Margaritas, pick some guy on his third tequila, and go for it. Just don't lose your house in the divorce like every other woman on this lake. Buy him out. Send him to some reasonably priced, brand-new shitbox in a subdivision. Keep your property."

Beneath her bronzer, Candace looked a little taken aback. "Gosh, Dutch," she said. "I didn't mean to make you upset."

I shook a bunch of bottles at her. "Which are the sleepiest?"

She pointed to a fat one with a tricky-looking cap. "Was it Benny?" she said. "Was it because I brought up crashing in the pass?"

"I'm having a bad day," I said, but only because there was no way to explain how I felt about Benny, my first husband, crashing his Super Cub, or about the search for the wreckage, that smoking black hole in the trees. Even now, forty-one years later. The loneliness. The lostness.

Not to mention what it had been like, being the first and only female homeowner on Diamond Lake. If I had been cute and skinny and agreeable like Candace, it might have been easier. But I was me. The rolled eyes during votes, the snickers when I tried to advocate for trash removal or speed bumps, the hands, the lesbo jokes, the cigars handed to me in tampon wrappers—which I laughed about, seething, but smoked—I got through it all. What hurt the worst were the wives, all of them women I had known for years, who dropped me off their Fur Rondy gala list every time I was single. And stuck me back on when I wasn't.

Excerpted from Nobody Gets Out Alive by Leigh Newman. Copyright © 2022 by Leigh Newman. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.