Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

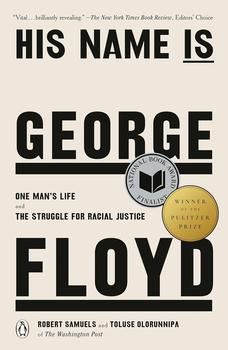

One Man's Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice

by Robert Samuels, Toluse Olorunnipa

"What up, gator?" Hall said, and the two shook hands.

It was close to noon by this point, so they stopped at a Wendy's across the street. Hall ordered a burger with onion rings; Floyd got a Dave's Double. After they carried the food to the Benz and unwrapped the sandwiches, Floyd took out his phone to show Hall a new trend in the world of Southern hip-hop.

"You know about sassa walking?" Floyd asked.

The men ate their burgers and watched music videos of the emerging sound--it contained the heavy, gritty beats of chopped-and-screwed songs, but rappers laced lighter, faster rhymes over the tracks. Some of the videos demonstrated the dance itself, which combined salsa steps with pelvic thrusts.

"It's gonna be big," Floyd said.

Next, they went to drop off Hall's borrowed truck and chilled in his hotel room at the Embassy Suites in Brooklyn Center, just on the other side of the Mississippi River. They ate Cheetos as Hall waited for some buyers to pick up drugs.

After someone came to pick up pills, Hall wanted to show off how successful he had become. He pulled out $2,000 in cash, telling Floyd he had made that much money in a single night. The display was more than a simple flex; Hall thought he might have a solution to Floyd's lingering malaise and hoped Floyd could use his connections in Houston to help boost his drug business. He said he believed he was offering Floyd a great opportunity. Floyd wasn't working; Hall had a bustling clientele, ready to pay.

But Floyd didn't give the idea too much thought, Hall recalled. He didn't want the drug game to be a part of his life ever again. He knew he was a bad hustler. And his last stint in prison had been so traumatizing that he was terrified of what might happen if he got caught up in it anew.

Hall also had to deliver drugs to buyers in different parts of the city, which was another reason he was happy to have Big Floyd around. Hall had become increasingly paranoid about driving himself to drug deals and thought Floyd could take the wheel. They made their way to another hotel twenty miles south, in Bloomington, where they ate sandwiches and drank Minute Maid Tropical Punch. Hall remembered Floyd smoking weed, snorting powdered fentanyl, and taking Tylenol.

As Hall fielded calls from potential buyers, Floyd was busy having conversations of his own. One of the people Floyd was communicating with that day was Shawanda Hill, his former lover.

"I want to see you," she texted him.

Back on the north side, Jackson returned to her house to find no charcoal, no lighter fluid, no car, no Floyd. Concerned by her friend's absence, she called to check in.

"Where are you?" Jackson asked.

"I'm about to see my girl," Floyd said. "I'll be back tonight."

Evening was beginning to fall, and Hall still wanted to drop off clothes at the dry cleaners, get a new cell phone, and shop for a tablet. He thought he could pick one up at a corner store on Minneapolis's south side called CUP Foods, which was known as a spot for buying and selling electronics for cheap. Floyd was a familiar face at CUP-managers said he'd stop by once or twice a week.

He told his old lover that he was on his way to the store. Hill, forty-five, was thrilled at that news--she needed to buy a new battery for her cell phone anyway, and she hoped to sneak a little Floyd time before picking up her granddaughter, whom she had promised to babysit that day. Hill boarded the #5 bus and headed down to the corner of East Thirty-Eighth Street and Chicago Avenue.

Hall and Floyd got to CUP Foods first. Hall walked to the back of the store, outside the view of the security cameras, and bought a tablet for $180. The manager said they needed some time to clean its hard drive, so instead of waiting around, Hall and Floyd headed about a mile north, to Lake Street, where Hall bought himself an iPhone 7.

It was close to seven thirty p.m. when the two friends circled back to CUP. Floyd parked the Benz across the street, and Hall went inside to pick up his tablet. He walked down the store's long, narrow aisles and past rows of fruits and vegetables to the electronics section, where locked glass display cases showcased tablets, laptops, and prepaid cell phones in bright green boxes. The cashier told Hall he needed to give him a refund because he had been unable to clear off the old files. Hall was still trying to figure out if there were any other options when Floyd came in a few minutes later. Floyd meandered around the front of the store, fumbling with cash in his pocket and saying hello to almost every employee he came across.

Excerpted from His Name Is George Floyd by Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa. Copyright © 2022 by Robert Samuels. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.