Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

My father came from a long line of apothecaries and sorcerers. There were no imperial appointments, nothing as grand as a jade seal or a French house in Beijing, but they did well for themselves, ensuring a kind of small immortality for magistrates and county governors.

Even after he came to the United States, he kept with him a tortoiseshell cabinet that was second in reverence only to the family altar. It gleamed black and calico with thirty small drawers on the front and at least fifteen secret ones hidden throughout. It contained a continent's wealth of dinosaur bones, mercury captive in small vials, powders and tinctures of all kinds.

Once in a while, an old man would come from Chinatown, bent and with all of his weight carried by the two hands clasped at the small of his back. There would be a hurried conversation with my father in the alley in back, which we shared with a Polish tailor.

These old men sat stoically on the rickety wooden chair we kept in the back while my father reached for his cabinet. He would grind and pour, slice and drown, and at the end, there would be a little green paper packet of immortality for the old men, cunningly folded to be tucked into a sleeve or a jacket.

My father spoke often of our ancestor Wu Li Huan, who had given the governor of Wu eight hundred years.

"Not a speck of gray in his hair, not a tremor in his writing hand," my father said.

The old men came for my father's potion two times, three or even four, but they never came after that. My father was no Wu Li Huan, and instead of centuries, he sold months and weeks.

My mother was the second generation to be born to the golden mountain, her English perfect, her Cantonese stilted. Her people hadn't even hoped to serve regional officials while they were in Guangzhou, which my father called home and she never did.

Her immortality, what tiny scraps of it she could claim, was in the trains that raced from coast to coast. Her father worked on the Chinese crews that broke ground for the iron tracks, sometimes only six inches a day through the frozen mountains. She told us he was an enormous man, bearded and broad with a face that was turned red by the cold of Montana.

He bellowed and bullied and coaxed so well that he sent money home, and in return was sent the ambitious village beauty.

To everyone's surprise, they loved each other and would have kept going on together forever if a premature blast had not dropped a mountain on his head, his and his crewmen's.

Forty men, and by then the exclusion acts had barred the way, so she was the only widow.

With her little daughter in tow, she went to live in Los Angeles where there were other Chinese, but she had had enough. When my mother could take a job at the Grandee Hotel at fourteen, her mother left for China, ready to be home.

Sometimes, when the wind blew just the right way, we could hear the trains whistling to each other from the yards, shrill cries of I am here, and do not stop me. When my mother heard them, her hair blackened slightly from ash to soot and the lines on her face grew just a little less deep.

Like we understood to make wide circles around the drunks on the streets and how calico cats were the luckiest of all, we understood immortality as a thing for men. Men lived forever in their bodies, in their statues, in the words they guarded jealously and the countries they would never let you claim. The immortality of women was a sideways thing, haphazard and contained in footnotes, as muses or silent helpers.

"But things are different here," my mother always said.

She had never set foot in China, would pass all her life on American soil, but she knew how different things could be. She clung to that, and so did we.

III

I ran back to the Comique as often as I could. When my mother gave me a nickel for my lunch, I would go hungry, feeding myself on dreams in black and silver, and then much, much later, miraculously and magnificently, in color. I ran errands for the neighbors when I could get away from the laundry, and when it had been too long since I had last sat on the painfully hard pine benches, I sold another inch of my hair.

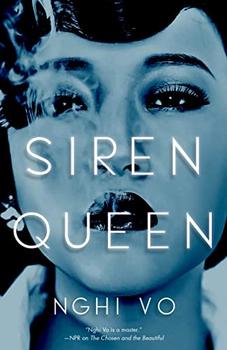

Excerpted from Siren Queen by Nghi Vo. Copyright © 2022 by Nghi Vo. Excerpted by permission of Tor.com. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.