Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

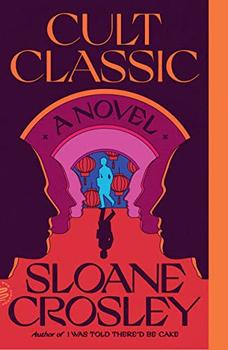

A Novel

by Sloane Crosley

Zach wound up overseeing the editorial page of a headhunting agency. The idea was that if Modern Psychology, the world's preeminent psychology periodical, had seen fit to employ Zach, he must be a people person. He must have insight into the needs of people. When they fired him, they cited a personality conflict. The fact that it took them six months to come to this conclusion was alarming. Generally speaking, being fired would've been a badge of honor for Zach. Alas, to be an unemployed headhunter was to be the butt of a joke that even he did not find funny. Disillusioned with corporate America and "the hoi polloi corruption of media," he went the practical route rather than settle for some "foggy facsimile" of culture. He entered the gig economy, delivering medical supplies, building bookshelves, drilling holes in the walls of useless liberal arts graduates, picking up dog medication for old ladies. He would've preferred to report to the dogs.

Of Clive's protégés, only I stayed the course. Or the closest to the course. I wound up running the arts and culture vertical of a site called Radio New York, the pet project of a venture capitalist who mostly left us alone. I farmed out bite-size nostalgia in the mode of lists of popular books and movies and podcasts, or assigned essays on popular books or movies or podcasts or think pieces responding to widely circulated essays on popular books or movies or podcasts. The Lloyd Dobler nightmare for the new millennium. Radio New York stifled every voice and clipped every word count. The culture of quotas and reviews was difficult for some (me) and a given for others (anyone under the age of thirty-five). But at least the specter of media decay felt different than it had at Modern Psychology, where the end of the magazine felt greater than itself. In the new media landscape, reduction was baked into the deal. Like going to work as a stunt double. Probably nothing bad will happen to you immediately but probably something bad will happen to you eventually.

"Is there any of that spicy cauliflower thing left?" asked Vadis, looking down the length of the table.

The table had been demonstrably cleared, all dishes replaced by dessert menus.

"I worry about you sometimes," said Zach.

"Worry about yourself," she said, patting him on the cheek.

He jerked his head back in a halfhearted way that suggested that cheek would go unwashed. I touched my jacket on the back of my chair. It was a thin army jacket, flammable, more for style than utility. I told myself I would leave it as self-imposed collateral.

In the beginning, these dinners were a lifeline to the past. The brainchild of Clive Glenn, our erstwhile king, they came with the air of leadership, no matter how neutered. Which is what we wanted and what we had lost. There was a time when we'd spent every moment with one another, arguing over articles like "Arguing Productively with Your Coworkers." We were shipwrecked from newsstands, kept alive by doctors' offices that allowed us to claim a staggering 17.5 pairs of eyes per copy. We were not invited to the cool parties (except, sometimes, Vadis) or the all-day Twitter wars (except, often, Zach) or the televised panels (except, toward the end, Clive). But we had low health insurance deductibles and we could stand the sight of one another.

Alas, even we were not spared from the shifting American attention span. Advertisers had clued in to the futility of the magazine ad, even in a targeted publication like ours. Print ads are like "tossing wet pasta down a well," said the rep for one account, a mixed metaphor that kept us amused—It puts the pasta down the well or else it gets the hose again—as we switched from monthly to bimonthly, from bimonthly to quarterly, from quarterly to online only, from online only to newsletter, from newsletter to dust.

Only Clive was somehow bolstered by this entire experience. Not unscathed, not like me, placed with some media host family until he found his forever home. Bolstered. Even when his name still crowned the masthead, he'd begun to step away from the drier aspects of running a magazine and morphing into a full-blown psych guru. He wrote the introduction to an anthology about psychic pain. He invented a DSM drinking game that he played at intimate dinner parties with celebrities who posted videos of the experience on their private social media accounts. When the videos leaked, he issued an apology for his insensitivity that landed him on NPR. He got his own talk show for a while, which was something. Tote bags appeared with the silhouette of his face on them. His speaking fees skyrocketed. But even Clive, with his Brain-Wise™ meditation kits and fancy friends, even Clive—well, I just never got the sense that any of us were as happy apart as we'd been together.

Excerpted from Cult Classic by Sloane Crosley. Copyright © 2022 by Sloane Crosley. Excerpted by permission of MCD. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Talent hits a target no one else can hit; Genius hits a target no one else can see.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.