Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

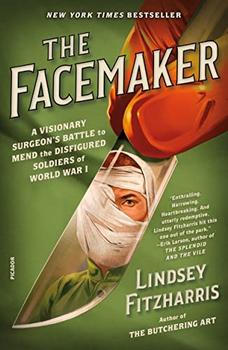

A Visionary Surgeon's Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I

by Lindsey Fitzharris

Gillies had always been a high achiever. He was a man for whom talent—be it athletic, artistic, or academic—was "mysteriously inherited rather than laboriously acquired," as his early biographer Reginald Pound observed. The youngest of eight children, Harold Gillies was born in Dunedin, New Zealand, on June 17, 1882. His grandfather John had immigrated there from the Scottish Isle of Bute in 1852, bringing his eldest son, Robert, along with him. Robert eventually set up business as a land surveyor, and it was in Dunedin that he met Emily Street, the woman who would become Harold's mother. The two fell in love and married shortly thereafter.

Gillies spent the first few years of his childhood tottering around the cavernous rooms of a Victorian villa. His father, an amateur astronomer, had commissioned the construction of an observatory with a revolving dome on the roof of their ornate stone residence. Robert Gillies christened the family home "Transit House." He chose the name in honor of the New Zealand astronomers who had made important observations of the 1874 transit of Venus when the planet passed across the face of the sun.

Gillies was a precocious child who loved to spend time roaming the expansive countryside around his home with his five older brothers, who would prop him up in the saddle of Brogo, the family mare, and bring him along on hunting and fishing expeditions. Early in life, Gillies fractured an elbow while sliding down the long banisters in the family home, which permanently restricted the range of motion of his right arm. It was a disability that later spurred him to invent an ergonomic needle-holder for use in the operating theater to compensate for his limited ability to rotate his hand.

Two days before his fourth birthday in June 1886, Gillies's idyllic childhood was shattered. That morning, one of his brothers climbed the stairs to check on their father, who had complained of feeling unwell the previous evening. When he entered the bedroom, he found Robert Gillies alert and in good spirits. His father told him that he would soon join everyone for breakfast in the dining room downstairs. The boy hurried off to tell his family the welcome news.

The kitchen sprang to life as pots and pans were pulled from high shelves, and the kettle whistled at the end of the water's slow boil. But as the minutes ticked by, Gillies's brother grew increasingly concerned. After half an hour, he climbed the grand staircase once more. A shock awaited him in the bedroom. Lying motionless on the mattress was Robert Gillies, dead from a sudden aneurysm at the age of fifty.

Following her husband's death, Gillies's mother moved herself and her eight children to Auckland so that they could be closer to her own family. When Gillies was eight years old, he was sent to England to attend Lindley Lodge, a boys' preparatory school near Rugby, in the heart of the country. Four years later, Gillies returned home to continue his education in New Zealand, but he wouldn't remain there for long. In 1900, at the age of eighteen, he moved back to England in order to study medicine at Cambridge University. His decision to become a doctor came as a surprise to everyone. It was a career he purported to have chosen to differentiate himself from his brothers, who were lawyers. "I thought another profession should be represented in the family," he joked.

At Cambridge, he gained a reputation for being something of a maverick after he spent his entire scholarship fund on a new motorcycle. He wasn't afraid to challenge his professors and could often be found arguing with the anatomical demonstrator in the university's dissection lab. Despite this lack of deference for authority, he was eminently likable and admired by teachers and classmates alike for "his happy temperament and his smile that broke into uproarious laughter." His popularity won him a nickname, "Giles," which stuck with him his entire life.

Excerpted from The Facemaker by Lindsey Fitzharris. Copyright © 2022 by Lindsey Fitzharris. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

People who bite the hand that feeds them usually lick the boot that kicks them

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.