Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

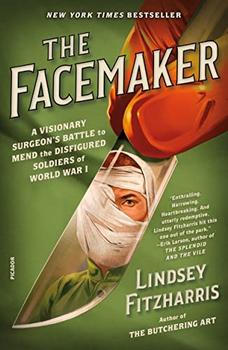

A Visionary Surgeon's Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I

by Lindsey Fitzharris

Gavrilo Princip—who, like Čabrinović, was also dying from tuberculosis and felt he had little to lose—could hardly believe his eyes. He took out his Browning Model 1910 semiautomatic pistol and took aim. Through good marksmanship or just dumb luck, he fatally wounded the royal couple. The first bullet passed through the door of the car, penetrating the duchess's abdomen and rupturing a stomach artery. The second bullet tore through the archduke's neck, severing his jugular vein. As the car sped off, the duchess fell into her husband's lap. Potiorek could hear Ferdinand whispering, "Sophie, Sophie, don't die, stay alive for our children," before he slipped into unconsciousness. Both were dead by eleven o'clock, just hours after they had arrived in Sarajevo.

A crowd descended on Princip, knocking the pistol from his hand as he raised it to his own temple. They kicked and clawed at him and probably would have killed him right then and there had police officers not managed to drag him away. Princip was later tried and sent to prison, where he wasted away from tuberculosis until he weighed less than ninety pounds. He died just weeks before the end of the global war that he had helped initiate.

The assassination was a catalyst of war, setting off a rapid chain of events that destabilized Europe due in part to a web of alliances that bound certain nations together. These alliances meant that if one country was attacked, the allied countries were obligated to defend it. On July 28—one month after the archduke was assassinated—Austro-Hungary declared war on Serbia. The very next day, imperial forces began to shell the Serbian capital of Belgrade. This declaration of war forced Russia to mobilize its troops, since it was bound by a treaty to defend Serbia, which in turn led Germany—allied with Austro-Hungary under the Triple Alliance agreement of 1882—to declare war on Russia. One by one, the fragile bonds of peace holding together the great powers of Europe began to loosen, and nation after nation slid inexorably into what would become the horror of World War I.

* * *

The escalating tension on the European continent received limited coverage in the British press. Articles about the situation were often buried deep inside newspapers. A debate about whether boxing was an appropriate spectator sport for women was commanding significantly more public interest. Over two thousand articles appeared on the subject in British newspapers in July 1914 alone, with headlines such as "Women at Boxing Matches. Is Their Presence Unbecoming?" The controversy over the influence of American ragtime music on British youth received similar interest.

The attitude of Britain's politicians toward events on the Continent was likewise dismissive. There was little enthusiasm in Parliament for a war in support of Serbia and her dictatorial ally, Tsarist Russia. Just eleven days before Britain entered the conflict, Prime Minster Herbert Asquith reassured his close friend Venetia Stanley that "happily there seems to be no reason why we should be anything more than spectators." Asquith—whose political party had come to power under the slogan "Peace, Retrenchment and Reform"—was more preoccupied with the looming threat of civil war in Ireland, where the prospect of home rule was dividing Nationalists and Unionists. The gathering storm in Europe seemed far away. By early August, however, it was clear that the coming conflict would not remain just another Balkan quarrel.

On August 3—two days after declaring war on Russia—Germany declared war on her ally France, hoping for a quick victory over the French before the slow-moving Russians could mobilize. Germany immediately began moving troops to the border of Belgium, which had been neutral by treaty since 1839. The German chancellor, however, dismissed the treaty as "a scrap of paper."

Excerpted from The Facemaker by Lindsey Fitzharris. Copyright © 2022 by Lindsey Fitzharris. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.