Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

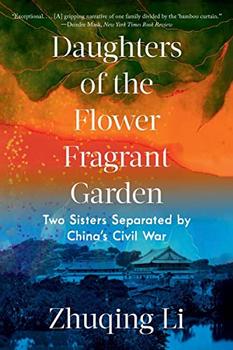

Two Sisters Separated by China's Civil War

by Zhuqing LiExcerpt

Daughters of the Flower Fragrant Garden

To be separated of course means having been together once, and Jun and Hong started out from the same place, a home named the Flower Fragrant Garden, a spacious, verdant family compound, one of Fuzhou's biggest and richest homes. It crowned what was called the Cangqian Hill across the Min River from the main part of Fuzhou, like a tiara encircled by a low stone wall. The main building was a grand, two-story red-brick Western-style house rising from the lush greenery of the rolling grounds. A winding path dipped under the canopy of green, linking smaller buildings like beads on a necklace.

Growing up, I knew of the Garden the way one might know of a big old house in town, no more than a noteworthy part of the scenery. My parents returned from their political exile in the countryside when I was ten, and they took up posts at the Teachers College next door to the Garden. They weren't senior enough to be assigned housing there, in the exclusive compound for the leaders of the university, so we lived instead in a more modest faculty apartment building not far away.

From there I used to go often to visit my maternal grandmothers who lived at the foot of the Cangqian Hill. Yes, I had two maternal grandmothers, a relic of the Old China, where wealthy men like my grandfather could, and often did, have more than one wife. There was Upstairs Grandma, who was Jun and Hong's biological mother; and there was Downstairs Grandma, my mother's mother. The front door of my Grandmas' home had a large hibiscus tree, and through its checker-work of leaves we could see pieces of the Garden on the peak of the hill.

The Garden looked down on us like something from a fairy tale, forbidding and aloof, off limits to ordinary people. Guards were posted at its main gate. I didn't know that in times past––when the Chen family, my mother's side of the family, was one of the wealthiest and most prominent in Fuzhou—it had owned the whole compound. Or that several branches of my extended family lived there under the same roof, where they raised many children, worshipped their ancestors, and celebrated the festivals in lavish style. During my girlhood, nobody in my family spoke of the place. But the trail that took me to school ran along the outside of the stone wall that encircled the Garden. I'd walk past a ditch that overflowed in every heavy rain, skirt an abandoned graveyard that always sped me up, and at the last turn, look out on a spectacular view of the Min River below where I'd pause to catch my breath.

So I knew of a hole in the otherwise impregnable wall, and one day when I was seven I went through it, pursuing a runaway ball. I lingered: the cicadas' buzz was especially intense there, so was the mélange of floral and fruity fragrances.

There was nobody inside the wall, only me and my ball. What captivated me was the gigantic and massive front door of the main building, fortified with a rich layer of red lacquer and two fierce lion-face bronze knockers too high for me to reach. It stood tauntingly ajar. My heart beating, I leaned all my weight on it, and it gave way a few inches, emitting a deep, throaty, scary growl. I flinched reflexively even as I peered within. The cavernous hall inside sent out a gush of cool air seeming to threaten to suck me into the vacuum of the house. I pulled away and ran for my life, but not until I paused for a glimpse of the porcelain toilet behind a half-closed door in a small outhouse before making my way back to the hole in the wall.

Nobody spoke of my Aunt Jun either, and this was perhaps even stranger. She was my Aunt Hong's older sister. The two of them had been nearly inseparable when they were girls, especially during the eight years of war with Japan when the Chen family was forced into an internal exile. But their lives were disrupted again by China's Civil War, and then they were abruptly separated when the bamboo curtain fell between Communist and non-Communist regions of China. Hong never mentioned to anyone in my generation that she even had a sister, much less a sister whose own life and associations had caused both emotional anguish and political trouble for the family in Communist China. By the time I came along, Hong had become a prominent physician in Fuzhou, famous as a pioneer in bringing medical care to China's remote countryside, and later the "grandma of IVF babies," in vitro fertilization, in Fujian Province. She was an important, unsentimental person, too busy perhaps to recount tales of days bygone. But none of my other aunts and uncles ever breathed a word either, about Jun or the Garden, to me or to my cousins. Not my own mother, not even Jun's own mother, my Upstairs Grandma, ever told me or my cousins that we had an aunt named Jun.

Excerpted from Daughters of the Flower Fragrant Garden: Two Sisters Separated by China's Civil War. Copyright (c) 2022 by Zhuqing Li. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

What really knocks me out is a book that, when you're all done reading, you wish the author that wrote it was a ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.