Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

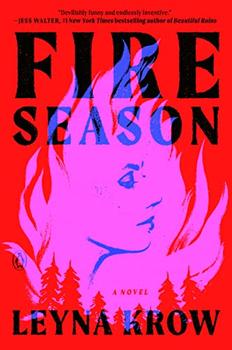

A Novel

by Leyna Krow

He backed away from the edge. He would have to do something else. He assured himself he would not dillydally. He would take his life in the privacy of his own house that very night. A public spectacle was not his style after all. Let the people of Spokane Falls learn of his demise later, through whispers and rumor, a haunting of sideways information. Did he really ... ? they'd ask whenever they passed the bank. And the answer would be Yes, he did.

He'd hang himself in his parlor as soon as he got home. There was an oak crossbeam above his doorway that would be perfect for the purpose.

Barton lived just north of downtown. His house was on a hill and from his front windows he could see Spokane Falls spread out before him. First, there was the river and the sawmill. Then there was the rail yard for the Northern Pacific. Then Railroad Avenue, with its cramped tenements to the east, city hall to the west, and Roslyn and the lunchroom in the middle. His bank, the post office, and a crush of bars and hotels of varying repute lined the blocks beyond that.

Up on his hill, Barton's house stayed cool. He left his windows open in the evenings, and he generally found this to be his happiest time of day. Indeed, he felt his mood lift upon entering the house. He decided he would eat something. No need to kill himself on an empty stomach. But after that, he'd do it.

So, he enjoyed a large dinner and pretended, as he ate, to be a man in a fine, if not enviable, state. He accomplished this trick of the mind by taking stock of all the people he knew who were not having a nice meal in their nice homes on nice hills. There was the barber who had mutilated Barton's already receding hairline. In retrospect, Barton was certain he had looked more than a little syphilitic. This man was likely studying his own complexion in a mirror at this very moment, overtaken by the horror of his disease, and by the poor choices that had landed him in such a state. Then there were Jim and Del Dweller, Barton's rude and ungrateful employees at the bank-twin brothers who lived together in a stuffy house by the river and who were so cheap they probably only ever ate boiled potatoes. And lastly, there was Barton's father, that hateful man who Barton felt certain was miserable in a variety of ways, though he could not imagine any specifically. Barton ate and thought of these people and their unpleasant situations. It bolstered him so thoroughly, he thought he might not want to end his life that night after all. But once this notion entered his mind, he chided himself for it. Coward, he thought, are you the sort who can't follow through on a plan?

He was just finishing his meal when the bells began to sound. They were alarm bells from downtown. They startled him from the depths of his own mind. He went outside. It was still light out, so bright in comparison to Barton's dining room that he had to squint, and at first he could not see anything wrong at all.

"What is it?" Barton shouted to his neighbor, who was standing on his own porch with his wife and daughter.

"A fire," the man shouted back, pointing.

Now he could see. In the sharp light of the northern evening, a red-orange pocket emerged in the distance. The fire was so new, or so hot, or so something else-Barton did not know what-that it had not yet begun to produce smoke. Later, the smoke would come, and ash, which would rain down on the town. But at first, it was just the flames.

The fire was across the river and past the rail yard, in the heart of downtown. Barton looked. He allowed the fire to draw his eyes. In its brightness, he received a wonderful sight: a sparkling vision of brilliance and possibility. Barton was not a religious man, but he felt he was being gifted something from beyond himself.

Here now was a valid excuse to wait another day.

2

Barton had come to Spokane Falls in Washington Territory in 1883. He moved from Portland at the age of twenty-three to escape his domineering father and his depressive, overbearing mother. Barton's father was a lawyer. At the time, Barton was most of the way through his own training in law, his father having decreed that Barton would follow in his footsteps. The man was cold, calculating, and always after Barton about something, always berating him for any misstep. Those papers are out of order. Those shoes are scuffed. Your brain is as small as your dick. Your mother swears you're mine but we never had any men as ugly on my side of the family. Now, six years later, Barton could not recall the exact breaking point, only that one day he'd been at his job clerking for a Portland judge and the next he'd been on a train north, then a wagon coach east, bound for a place where silver had been discovered and any young man willing to work could make good for himself in the mines. This was what Barton wanted: to make good for himself. Himself and no one else.

Excerpted from Fire Season by Leyna Krow. Copyright © 2022 by Leyna Krow. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.