Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

IN FLUX

It begins with What are you? hollered from the perimeter of your front yard when you're nine—younger, probably. You'll be asked again throughout junior high and high school, then out in the world, in strip clubs, in food courts, over the phone, and at various menial jobs. The askers are expectant. They demand immediate gratification. Their question lifts you slightly off your preadolescent toes, tilting you, not just because you don't understand it, but because even if you did understand this question, you wouldn't yet have an answer.

Perhaps it starts with What language is your mother speaking? This might be the genesis, not because it comes first, but because at least on this occasion you have some context for the question when it arrives.

You immediately resent this question.

"Why's your mother talk so funny?" your neighbor insists.

Your mother calls to you from the front porch, has called from this perch overlooking the sloping yard since you were allowed to join the neighborhood kids in play. Always, this signals that playtime is over, only now shame has latched itself to the ritual.

Perhaps you'd hoped no one would ever notice. Perhaps you'd never noticed it yourself. Perhaps you ask in shallow protest, "What do you mean, 'What language'?" Maybe you only think it. Ultimately, you mutter, "English. She's speaking English," before going inside, head tucked in embarrassment.

In this moment, for the first time, you are ashamed of your mother, and you are ashamed of yourself for not defending her. More than to be cowardly and disloyal, though, it's shameful to be foreign. If you've learned anything during your short residence on earth, you've learned this.

It's America and it's the eighties, and at school, in class, you pledge to one and one flag only, the Stars and Stripes. Greatest country on earth is the morning anthem. It's the lesson plan, a mantra, drilled into you day in, day out—a fact as inarguable as two plus two equaling four—and what you start to hear, as you repeat this to yourself, is the implication that all other nations, though other nations are seldom mentioned in school, are inferior.

You believe this.

It's an easy lesson to internalize, except that your brother, Delano; your parents; nearly all your living relatives are Jamaican. When your play cousin moves from Kingston to Miami, to your Cutler Ridge neighborhood, winding up in your third-grade class, refusing to pledge allegiance to your flag, you know to distance yourself from her. You say a quiet thanks that your last names are different.

If you'd had any context for the question of what you "are" when it first came, you might have answered, American.

You were born in the United States and you've got the paperwork to prove it. You feel pride in this fact, this inalienable status. You belt Lee Greenwood's "God Bless the U.S.A." on the Fourth of July, and even more emphatically after visiting your parents' island nation for two weeks in your ninth summer. You disagree with every aspect of the island life, down to the general lack of central air-conditioning. You prefer burgers and hot dogs to jerked or curried anything.

Back at home your parents accuse you of speaking, and even acting, like a real Yankee. But if by Yankee they mean American, you embrace it. "I speak English," you respond.

Your parents' patois and what many deem an indecipherable accent still play as normal, almost unnoticeable against your ears, except that it is increasingly paired with the punitive. For instance, when your mother says, "Unoo can spill di t'ing on di tile, but unoo can' clean it?"

And your brother says, "No me, Mummy."

And you say, "I didn't do it, Mom."

She'll say, "Den who did? Mus' be a duppy."

The duppy becomes the scapegoat for all the inexplicable activity that takes place in and outside your house. The duppy broke your mother's vase, then tried to glue it back together. The duppy hid your brother's report card underneath his mattress. The duppy possessed your father, dragged his body out for drinks after work, and didn't bring him home until morning.

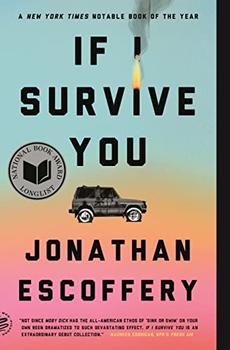

Excerpted from If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery . Copyright © 2022 by Jonathan Escoffery . Excerpted by permission of MCD. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Heaven has no rage like love to hatred turned, Nor hell a fury like a woman scorned.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.