Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

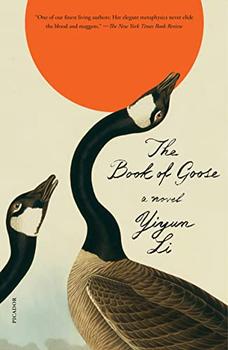

A Novel

by Yiyun LiExcerpt

The Book of Goose

YOU CANNOT CUT AN APPLE with an apple. You cannot cut an orange with an orange. You can, if you have a knife, cut an apple or an orange. Or slice open the underbelly of a fish. Or, if your hands are steady enough and the blade is sharp enough, sever an umbilical cord.

You can slash a book. There are different ways to measure depth, but not many readers measure a book's depth with a knife, making a cut from the first page all the way down to the last. Why not, I wonder.

You can hand the knife to another person, betting with yourself how deep a wound he or she is willing to inflict. You can be the inflicter of the wound.

One half orange plus another half orange do not make a full orange again. And that is where my story begins. An orange that did not think itself good enough for a knife, and an orange that never dreamed of turning itself into a knife. Cut and be cut, neither interested me back then.

MY NAMES IS AGNÈS, but that is not important. You can go into an orchard with a list of names and write them on the oranges, Françoise and Pierre and Diane and Louis, but what difference does it make? What matters to an orange is its orange-ness. The same with me. My name could have been Clémentine, or Odette, or Henrietta, but so? An orange is just an orange, as a doll is a doll. Don't think that once you name a doll, it is different from other dolls. You can bathe it and clothe it and feed it empty air and put it to bed with the lullabies you imagine a mother should be singing to a baby. All the same, the doll, like all dolls, cannot even be called dead, as it was never alive.

The name you should pay attention to in this story is Fabienne. Fabienne is not an orange or a knife or a singer of lullabies, but she can make herself into any one of those things. Well, she once could. She is dead now. The news of her death arrived in a letter from my mother, the last of my family still living in Saint Rémy, though my mother was not writing particularly to report the death, but the birth of her own first great-grandchild. Had I remained near her, she would have questioned why I have not given birth to a baby to be added to her collection of grandchildren. This is one good thing about living in America. I am too far away to be her concern. But long before my marriage I stopped being her concern—my fame took care of that.

America and fame: they are equally useful if you want freedom from your mother.

In the postscript of the letter, my mother wrote that Fabienne died the previous month—"de la même manière que sa sœur Joline"—in the same manner as her sister. Joline had died in 1946 in childbirth, when she was seventeen. Fabienne died in 1966, at twenty-seven. You would think twenty years would make childbirth less a killer of women, you would think the same calamity should never strike a family twice, but if you think that way you are likely to be called an idiot by someone, as Fabienne used to call me.

My first reaction, after I read the postscript: I wanted to get pregnant right away. I would carry a baby to term and I would give birth to a child without dying myself—I knew this with the certainty that I knew my name. This would be proof that I could do something Fabienne could not—be a bland person, who is neither favored nor disfavored by life. A person without a fate.

(This desire, I imagine, can be truly understood only by people with a fate, so it is a desire akin to wishful thinking.)

But you need two people to get pregnant; and then two people do not necessarily guarantee success. Getting pregnant, in my case, would involve looking for a man with whom I could cheat on Earl (then what—explaining to him a bastard would still be better than a barren marriage?), or divorcing him for a man who can sow and reap better. Neither appeals to me. Earl loves me, and I love being married to him. The fact that he cannot give me a child may be disheartening to him, but I have told him that I did not marry him to become a mother. In any case we are both realists.

Excerpted from The Book of Goose by Zhuqing Li. Copyright © 2022 by Zhuqing Li. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.