Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

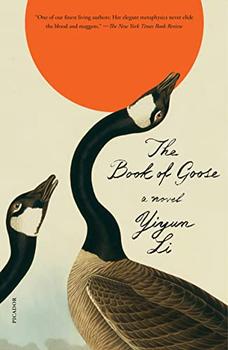

A Novel

by Yiyun Li

Earl left the Army Corps of Engineers after we moved back from France and now works for his father, a well-respected contractor. I have a vegetable garden, which I started in our backyard, and I raise chickens, two dozen at any time. I was hoping to add to my charges some goats, but the two kids I acquired had a habit of chewing the wooden fence and running away. Lancaster, Pennsylvania, is not Saint Rémy, and I cannot turn myself back into a goatherd. "A French bride" is how I was first known to the local people, and some, long after I stopped being a new wife (we have been married for six years now), still refer to me by that name. Earl likes it. A French bride adds luster to his life, but a French bride chasing goats down a street would be an embarrassment.

I gave up the goats and decided to raise geese instead. Last spring, I acquired my first two, a pair of Toulouse geese, and this year I purchased a pair of Chinese geese. Earl read the catalogue and joked that we should go on adding American geese and African geese and Pomeranian geese and Shetland geese each year. Let's have a troupe of international brigands, he said. But he forgot that the two couples will soon be parents. In a year I will be expecting goslings.

The geese, more than the chickens, are my children. Earl likes the geese, too, and he was the one to suggest that we give them French names. His French is not as good as he thinks, but that has not stopped him from speaking the language to me in our most intimate moments. I always speak English to the people in my American life. I speak English to my chickens and geese.

The garden produces more vegetables than we can consume. I share them with my in-laws—Earl's parents and his two brothers and their families. They are all nice to me, even though they find me foreign, and perhaps laughable. They call me Mother Goose behind my back. This I learned from Lois, my sister-in-law, who is unhappily married and who hopes to turn me against the Barrs family. I don't mind the nickname, though. It may be insensitive of them to call a childless woman Mother Goose, but I am far from being a sensitive or sentimental woman.

When Earl asked about my mother's letter, I told him about the birth of my grandniece, but not the death of Fabienne. If he detected anything unusual, he would assume that another baby's birth reminded me of the void in my life. He is a loving husband, but love does not often lead to perception. When I met him, he thought I was a young woman with no secrets and few stories from my childhood and girlhood. Perhaps it is not his fault that I cannot get pregnant. The secrets inside me have not left much space for a fetus to grow.

I was in such a trance that I forgot to separate the geese from the chickens at their mealtime. The geese had a busy time terrorizing and robbing the chickens. I chastised them without raising my voice. Fabienne would have laughed at my incompetency. She would have told me that I should simply give the geese a good kick. But Fabienne is dead. Whatever she does now, she has to do as a ghost.

I would not mind seeing Fabienne's ghost.

All ghosts claim their phantom skills: to shape-shift, to haunt, to see things we don't see, to determine how the lives of the living people turn out. If dead people had no choice but to become ghosts, Fabienne's ghost would only scoff at the usual tricks that other ghosts take pride in. Her ghost would do something entirely different.

(Like what, Agnès?

Like making me write again.)

No, it is not Fabienne's ghost that has licked the nib of my pen clean, or opened the notebook to this fresh page, but sometimes one person's death is another person's parole paper. I may not have gained full freedom, but I am free enough.

"HOW DO YOU GROW HAPPINESS?" Fabienne asked. We were thirteen then, but we felt older. Our bodies, I now know, were underdeveloped, the way children born in wartime and growing up in poverty are, with more years crammed into their brains. Well-proportioned we were not. Well-proportioned children are a rare happenstance. War guarantees disproportion, but during peacetime other things go wrong. I have not met a child who is not lopsided in some way. And when children grow up, they become lopsided adults.

Excerpted from The Book of Goose by Zhuqing Li. Copyright © 2022 by Zhuqing Li. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.