Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

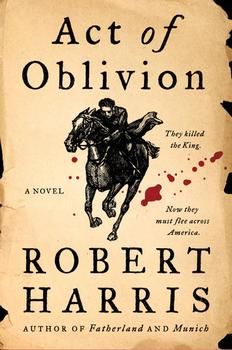

A Novel

by Robert Harris

Mary, sitting on the bed, heard the boards creak as they passed. She glanced at her husband. 'What now, do you suppose?' she whispered. He shook his head, had no idea.

The two officers passed through the parlour, out into the front yard, through the gate, and set off down the slope to the river.

Gookin had taken them straight from the Prudent Mary to the home of the governor, John Endecott, an old man in a lace collar and black cap who seemed to Ned to have stepped out of the England of Queen Elizabeth. They had handed him their letters of introduction – Will's from John Rowe and Seth Wood, the preachers at Westminster Abbey, Ned's from Dr Thomas Goodwin of the Independent Church in Fetter Lane – and while the old man held them close to his eyes and studied them, Ned had sketched the circumstances of their departure: how for two days at Gravesend they had been obliged to hide below decks while on the quayside the common people had celebrated the imminent return of Charles II, son of the dead king. The sky above the town had glowed a diabolic red from their bonfires, the air had been filled with the noise of their carousing and the sizzle of their roasting meat. The revels had gone on disgracefully late into the Sabbath. On the Monday, when news was brought from Parliament that his name and Will's were on the list of those wanted for the death of Charles I, Captain Pierce had given the order to put to sea.

'But for our good friend Mr Gookin here,' concluded Ned, 'we were likely to have been taken.'

'So you both were judges of the King?'

'Yes, and signed his death warrant. And let me be plain with you, Mr Endecott, for I would not live here under false pretences. We would do the same tomorrow.'

'Would you indeed!' Endecott set down the letters and studied the two visitors through moist occluded eyes, pale grey as oysters. He gripped the edge of his desk. Amid a fusillade of cracking joints, he pulled himself to his feet. 'Then let me shake the hands that signed it, and bid you welcome to Massachusetts. You will find yourselves among good friends here.'

They scouted out a place a little way off the road, where part of the riverbank had been eroded by the current to form a natural pool. Trees hung down almost to the surface. Someone had tied a rope to a branch to make a swing. A long green dragonfly, more exotic than anything they had seen in England, skimmed between the reeds. Wood pigeons cooed amid the foliage. Ned pulled off his boots and briefly dipped his feet into the cool flow, then stripped off his brine-stiffened clothes and waded naked into the river. The cold made him shout out loud. He ducked his shoulders beneath the surface until after a minute he became used to the temperature. On the bank, Will had taken off his own boots and leather coat but seemed to be hesitating. Ned waded back, cupped his hands full of water and splashed him. Will laughed, danced away and shouted in protest, then pulled his shirt over his head and quickly removed the rest of his clothes.

What a sight they made, thought Ned, with their dead white bodies and their battle scars, like phantoms amid all this lush greenery. He'd seen corpses that looked better. Their skin, front and back, was covered in nicks and welts. Will had a jagged line across his stomach from a royalist pike at Naseby, he himself an ugly fist-sized crater beneath his right shoulder, sustained when he was knocked off his horse at Dunbar. Will stood on the water's edge and lifted his arms above his head. At forty-two, he was still slender as a boy. To Ned's surprise he launched himself into a dive, full-length. He disappeared beneath the surface, then bobbed up moments later.

Was there any sensation more delicious than this – to wash stale salt off sweating skin in fresh water on a summer's day? Praise God, praise God in all His glory, for bringing us in safety to this place! Ned flexed his toes in the soft mud. It was years since he had swum. He was always poor in the water, even as a boy. But he stretched out his arms and allowed himself to topple forwards, and presently rolled over onto his back. Katherine floated into his mind, and for once he did not try to shut out the memory, but allowed her to take shape. Where was she? How was she? It was four years since she had miscarried and almost died, and her health and spirit had never properly recovered. But what was the use of tormenting himself, as Will did every night, with impossible speculations? One of them must be strong. They had a duty to stay alive, not for themselves but for the cause. His text, which in the end was what had persuaded Will to join him, was Christ's injunction to his disciples: 'But when they persecute you in this city, flee ye into another; for verily I say unto you, Ye shall not have gone over the cities of Israel, till the Son of man be come.'

Excerpted from Act of Oblivion by Robert Harris. Copyright © 2022 by Robert Harris. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.