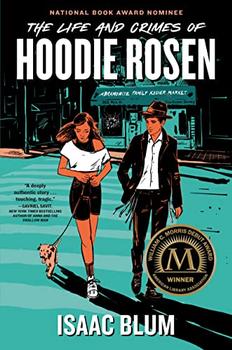

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

CHAPTER 1

in which I celebrate Tu B'Av by taking the first step toward my own ruination

LATER, I TRIED TO EXPLAIN to Rabbi Moritz why it was ironic that my horrible crime was the thing that saved the whole community. He didn't get it, either because he was too angry, or because his head was filled with other thoughts, or because the man has no sense of humor.

I don't think it's funny now—it ruined my life, put me in intensive care, and humiliated me and my family on a global scale. But I found it funny at the time.

It all started on Tu B'Av, which is one of the more obscure Jewish holidays. I'm Orthodox, but even I couldn't recall what the holiday was about. I only remembered when I looked out the window and saw the girl in white. She was on the sidewalk across the street.

I was in halacha class, learning about Jewish law. We were talking about ritual hand-washing. Rabbi Moritz paced back and forth in front of the whiteboard, reading from the Shulchan Aruch, making the occasional Hebrew or English note on the board.

I was a little distracted because Moshe Tzvi Gutman was slurping cereal next to me, and a little distracted because Ephraim Reznikov was reading his copy of the Shulchan Aruch out loud but out of sync with Rabbi Moritz. But I was mostly distracted trying to remember what the heck Tu B'Av was about.

I couldn't ask my buddy Moshe Tzvi because he would make fun of me for not knowing. Moshe Tzvi studies really hard, and he makes you feel like an ignorant schmuck if you aren't as learned as he is. So I just stared out the window as though the answer would be out on the street. And then it was.

Because now the girl was dancing, making various motions with her hands, swinging her body around in little circles.

Which made me remember that Tu B'Av had something to do with dancing girls and the grape harvest—the grape harvest was pretty big back in biblical times. During the grape harvest, all the unmarried girls of Jerusalem went out into the vineyards where the harvest was happening, and they danced, wearing only plain white robes. Because all these girls were wearing plain white robes, the boys didn't know if the girls were rich or poor, or even which tribe they were from. It created a level playing field, and the boys could choose a wife without thinking about if she was poor, or if she was from some undesirable rival tribe.

The girl outside wasn't wearing a white robe, because it was the twenty-first century. She wore a white T-shirt, its short sleeves revealing skinny arms. The shirt ended just above a pair of shorts that left most of her legs exposed. The legs ended at a pair of white Adidas sneakers, striped blue.

She was dancing. But why was she dancing? There was nobody on the sidewalk with her but a small white dog. I thought it was strange behavior, but maybe gentile girls danced for their dogs all the time. I had no idea. I wasn't supposed to look at gentile girls. I guess there were Jewish girls who dressed that way too, but certainly not any I knew. And if she was a Jewish girl dressed like that, I wasn't allowed to look at her either.

When she stopped dancing, she walked over to the base of a tree, bent down, and picked up a cell phone. Maybe she'd recorded her dance? She stood up, looked over, and made eye contact with me. Or, I thought she did. It was hard to tell from that distance, but when she looked up at me—or at the school—I reflexively looked away, up at the board, at Rabbi Moritz. The contrast between the girl and the rebbe couldn't have been starker. He wore a heavy black suit and had an enormous beard. And Moritz was spitting as he talked. He had a little bit of saliva on his upper lip.

"Why, according to the text," the rebbe asked, "must we wash our hands upon rising in the morning? Why, before we walk four cubits, must we wash?"

Excerpted from The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen by Isaac Blum. Copyright © 2022 by Isaac Blum. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.