Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

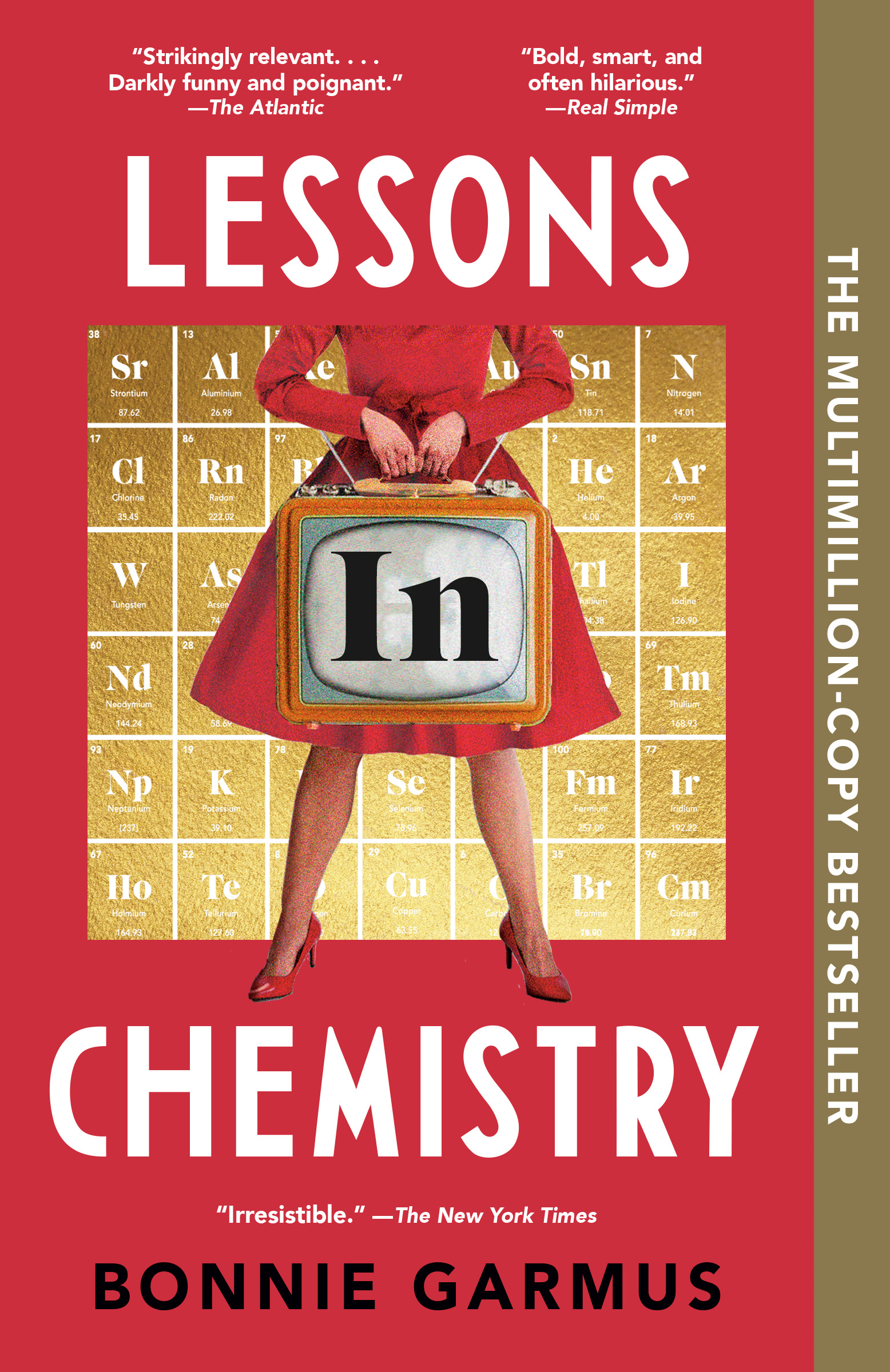

by Bonnie GarmusHastings Research Institute

Ten Years Earlier, January 1952

Calvin Evans also worked at Hastings Research Institute, but unlike Elizabeth, who worked in crowded conditions, he had a large lab all to himself.

Based on his track record, maybe he deserved the lab. By age nineteen, he had already contributed critical research that helped famed British chemist Frederick Sanger clinch the Nobel Prize; at twenty-two, he discovered a faster way to synthesize simple proteins; at twenty-four, his breakthrough concerning the reactivity of dibenzoselenophene put him on the cover of Chemistry Today. In addition, he'd authored sixteen scientific papers, received invitations to ten international conferences, and had been offered a fellowship at Harvard. Twice. Which he turned down. Twice. Partly because Harvard had rejected his freshman application years earlier, and partly because--well, actually, there was no other reason. Calvin was a brilliant man, but if he had one flaw, it was his ability to hold a grudge.

On top of his grudge holding, he had a reputation for impatience. Like so many brilliant people, Calvin just couldn't understand how no one else got it. He was also an introvert, which isn't really a flaw but often manifests itself as standoffishness. Worst of all, he was a rower.

As any non-rower can tell you, rowers are not fun. This is because rowers only ever want to talk about rowing. Get two or more rowers in a room and the conversation goes from normal topics like work or weather to long, pointless stories about boats, blisters, oars, grips, ergs, feathers, workouts, catches, releases, recoveries, splits, seats, strokes, slides, starts, settles, sprints, and whether the water was really "flat" or not. From there, it usually progresses to what went wrong on the last row, what might go wrong on the next row, and whose fault it was and/or will be. At some point the rowers will hold out their hands and compare calluses. If you're really unlucky, this could be followed by several minutes of head-bowing reverence as one of them recounts the perfect row where it all felt easy.

Other than chemistry, rowing was the only thing Calvin had true passion for. In fact, rowing is why Calvin applied to Harvard in the first place: to row for Harvard was, in 1945, to row for the best. Or actually second best. University of Washington was the best, but University of Washington was in Seattle and Seattle had a reputation for rain. Calvin hated rain. Therefore, he looked further afield--to the other Cambridge, the one in England, thus exposing one of the biggest myths about scientists: that they're any good at research.

The first day Calvin rowed on the Cam, it rained. The second day it rained. Third day: same.

"Does it rain like this all the time?" Calvin complained as he and his teammates hoisted the heavy wooden boat to their shoulders and lumbered out to the dock. "Oh never," they reassured him,

"Cambridge is usually quite balmy." And then they looked at one another as if to confirm what they had already long suspected: Americans were idiots.

Excerpted from Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus. Copyright © 2022 by Bonnie Garmus. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

In youth we run into difficulties. In old age difficulties run into us

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.