Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

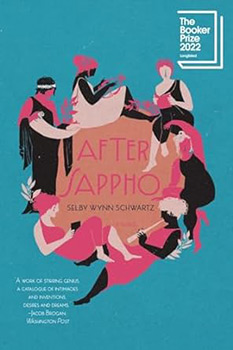

by Selby Wynn SchwartzAfter Sappho, by Selby Wynn Schwartz

The problems of Albertine are

(from the narrator's point of view)

a) lying

b) lesbianism,

and (from Albertine's point of view)

a) being imprisoned in the narrator's house.

—Anne Carson, The Albertine Workout

Sappho, c. 630 BCE

The first thing we did was change our names. We were going to be Sappho.

Who was Sappho? No one knew, but she had an island. She was garlanded with girls. She could sit down to dine and look straight at the woman she loved, however unhappily. When she sang, everyone said, it was like evening on a riverbank, sinking down into the moss with the sky pouring over you. All of her poems were songs.

We read Sappho at school, in classes intended merely to teach poetic meter. Very few of our teachers imagined that they were swelling our veins with cassia and myrrh. In dry voices they went on about the aorist tense, while inside ourselves we felt the leaves of trees shivering in the light, everything dappled, everything trembling.

We were so young then that we had never met. In back gardens we read as much as we could, staining our dresses with mud and pine-pitch. Some of us were sent by our families to distant schools to be finished, so that we would come to our proper end. But it was not our end. It was barely our beginning. Each one lingered in her own place, searching the fragments of poems for words to say what it was, this feeling that Sappho calls aithussomenon, the way that leaves move when nothing touches them but the afternoon light.

At that time we were not called anything and so we cherished every word, no matter how many centuries dead. Reading of the nocturnal rites of the pannuchides we stayed up all night; the exile of Sappho to Sicily turned our eyes to the sea. We began writing odes to clover blossoms and blushing apples, or painting on canvases that we turned to the wall at the slightest sound of footsteps. A sidelong glance, a half-smile, a hand that rested on our arms just above the elbow: we had not yet memorized the lines for these occasions. Or there were only fragments of lines that we could have offered, in any case. Of the nine books of poems written by Sappho, mere shreds of dactyls survive, as in Fragment 24C: we live/…the opposite/…daring.

CHAPTER ONE

Cordula Poletti, b. 1885

Cordula Poletti was born into a line of sisters who didn't understand her. From the earliest days, she was drawn toward the outer reaches of the house: the attic, the balcony, the back window touched by the branches of a pine tree. At her christening she kicked free of the blankets bundled around her and crawled down the nave. It was impossible to swaddle Cordula long enough to name her.

Cordula Poletti, c. 1896

Whenever she could, she took a Latin primer from the Biblioteca Classense and went to sit in a tree near the cemetery. In her house they called, Cordula, Cordula!, and no one would answer. Finding Cordula's skirts discarded on the floor, her mother openly despaired of her prospects. What right-minded citizen of Ravenna would marry a girl who climbed up the trees in her underthings? Her mother called, Cordula, Cordula?, but there was no one in the house who would answer that question.

X, 1883

Two years before the christening of Cordula, Guglielmo Cantarano published his study of X, a twenty-three-year-old Italian. In excellent health, X went whistling through the streets and kept a string of girlfriends happy. Even Cantarano, who disapproved, had to admit that X was jovial and generous. X would throw a shoulder to a wheel without complaint, could make a room roar with laughter. It wasn't that. It was what X was not. X was not a willing housewife. X remained unmoved by squalling infants, would not wear skirts that swaddled the stride, had no desire to be pursued by the hot breath of young men, failed to enjoy domestic chores, and possessed none of the decorous modesty of maidenhood. Whatever X was, Cantarano wrote, it was to be avoided at all costs.

Excerpted from After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz. Copyright © 2023 by Selby Wynn Schwartz. Excerpted by permission of Liveright/W.W. Norton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.