Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

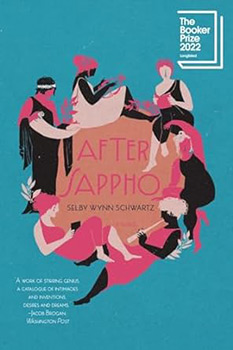

A Novel

by Selby Wynn Schwartz

We could picture Lina in those years: her high buttoned boots, her erudite citations. Above her boots she seemed hardly to be wearing skirts. Lina Poletti was like that, she could make visible things seem scant and unremarkable. She had her own ways of escaping the century.

Sappho, Fragment 2

A kletic poem is a calling, both a hymn and a plea. It bends in obeisance to the divine, ever dappled and shining, and at the same time it calls out to ask, when will you arrive? Why is your radiance distant from my eyes? You drop through the branches when I sleep at the roots. You pour yourself out like the light of an afternoon and yet somewhere you linger, outside the day.

It is while invoking the one who abides and yet must be called, urgently, from a great distance, that Sappho writes of aithussomenon, the bright trembling of leaves in the moment of anticipation. A poet is always living in kletic time, whatever her century. She is calling out, she is waiting. She lies down in the shade of the future and drowses among its roots. Her case is the genitive of remembering.

Lina Poletti, c, 1905

Lina Poletti fought to sit in a chair at the library. She fought to smoke in the Caffè Roma-Risorgimento. She fought to frequent literary gatherings in the evenings. She did up her cravat with determined fingers and presented herself in public, over and over, to murmurs in Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II.

She went on, against the wishes of her family, to the university in Bologna. She studied under the esteemed poet Giovanni Pascoli, who was surprised to find her there. He peered at her, although she was sitting clearly in the front row of the lecture hall with her pen ready. There weren't many women who wanted to write a thesis on the poetry of Carducci. People were always saying that about Lina Poletti: they were surprised to find her, there weren't many like her. It was true that she had very striking eyes, with golden rims around her pupils. She seemed volatile, alchemical. Something might flash through her and change everything. As Sibilla Aleramo would say to us later, Lina was a violent, luminous wave.

CHAPTER TWO

Rina Faccio, b. 1876

As a girl, Rina Faccio lived in Porto Civitanova and did what she was told. Her father told her to work in the accounting department of his factory, and she did it. She was twelve years old, dutiful, with long dark hair.

In the factory glass bottles were produced, thousands every day, tinting the air with ferrous smoke. Rina was charged with the figures, how much sodium sulfate was carried to the furnace on the shoulders of how many portantini, the boys who worked eight hours a day for one lira. There was no school in Porto Civitanova, so Rina tried to teach herself how to account for all of this.

Rina Faccio, 1889

In 1889 Rina's mother told her something wordlessly that she never forgot. Her mother was standing at the window, looking out, in a white dress that hung off her shoulders. Then suddenly her mother went out the window. She plummeted, her dress trailing like a scrap of paper. Her body landed two floors down, bent into a bad shape. That was what Rina Faccio's mother had to say to her.

Nira and Reseda, 1892

Nira was the first time Rina changed her name. She wanted to write for the provincial local papers, but she was afraid that her father would find out.

When Rina Faccio turned fifteen, she grew out of anagrams. She chose the name Reseda because it reminded her of recita, a verb for actresses: it means, she plays her role, she recites her part. When her father thundered in the drawing-room about the opinions of these hussies, whoever they were, appearing in print, Rina Faccio looked up from her needlepoint as blank as a page.

Rina Faccio, 1892

Despite having been warned wordlessly by her mother, Rina Faccio didn't foresee her fate. She was obediently adding and subtracting numbers about the factory, keeping the ledgers in straight lines. A man who worked at the factory was moving in circles around her. He had brute hands that fastened on levers, a breath that crawled up the back of her neck. She didn't see him until the circles were very tight, and then it was too late. Her dress was shoved up. She cried out, but only the brute palm of his hand could hear her.

Excerpted from After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz. Copyright © 2023 by Selby Wynn Schwartz. Excerpted by permission of Liveright/W.W. Norton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.