Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

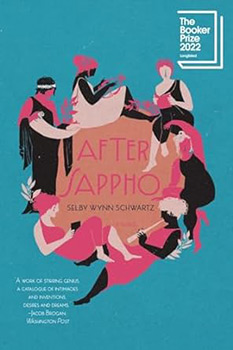

A Novel

by Selby Wynn Schwartz

Rina Pierangeli Faccio, 1893

Once Rina's father learned that she had been possessed by that man, there was nothing to do but transfer her to him in name and deed. Articles of Italian law bound a daughter into becoming a wife at the word of her father. In particular Article 544 of the Penal Code was like an iron lever, maneuvering girls of sixteen into position as brides to the very men who had trampled them down.

In the winter Rina was handed from one household to another, sallow and dazed. In the house of Rina's father, her two sisters sat silently at their needlepoint while her mother, or what was left of her, was consigned to the asylum at Macerata. There were no words for what happened in the house of the husband to whom Rina now belonged. After Rina Pierangeli Faccio had been delivered to him, along with some dining-room furniture, the curtains were drawn. When in the early months she miscarried in a feverish rush of blood, she did not ask why. But she felt welling up in her a tumultuous hatred of life, this life, her life.

The Pisanelli Code, 1865

The politicians hailed the Pisanelli Code as a triumph of the unification of Italy. The new state was eager to grow into its full shape, stretching the length of the entire peninsula and covering the populace with its laws. As one politician said, We made Italy; now we have to make the Italians.

Under the Pisanelli Code, Italian women gained two memorable rights: we could make wills to distribute our property after our own deaths, and our daughters could inherit things from us. Our writing before death had never seemed so important. Those of us in Italy considered whether we might bequeath to our daughters some small gift that could be pawned for a future.

Rina, 1895

In 1895, amid laundry and bruises, Rina Pierangeli Faccio gave birth to the child of that man. It was a son. When the infant turned two, she found the bottle of laudanum and wordlessly took all of it.

The laudanum didn't kill Rina Pierangeli Faccio, but it ended her days as a dutiful wife. The woman she had been until that night was dead, she said. The doctor prescribed bed-rest, the husband reproached her. But Rina would only speak to her sister.

Often that was the first thing we did when we were changing: we would find a sister and stay with her, taking breakfast in our room. Or we would find someone in her room and stay with her, pretending if needed that we were sisters. The housekeepers would widen their eyes, but if we prevailed, milky tea and toast were served in our room, on trays that spanned the whole width of our bed.

Dr. T. Laycock, A Treatise on the Nervous Disorders of Women, 1840

The eminent Doctor Laycock of York, writing on the nervous disorders of women, could not help but notice that the more young women consorted with each other, the more excitable and indolent they became. This condition might strike seamstresses, factory girls, or any woman who associated with any number of other women.

In particular, he cautioned, young females cannot associate together in public schools without serious risk of exciting the passions, and being led to indulge in practices injurious to both body and mind. Novels, whispers, unsigned poems, general education, shared sleeping compartments: no sooner were girls reading in bed than they were reading in bed together. What might look like sisterly affection or a schoolgirl's fancy ought to be diagnosed as the pernicious antecedent of hysteric paroxysms. In the throes of it they were highly contagious and might throw whole households into disorder.

Anna Kuliscioff, b. c. 1854

Before Anna Kuliscioff spent her life fighting for the rights of Italian women, she was born in southern Ukraine. As soon as she was old enough to grasp the basic idea of human life, she began explaining its principles to those around her, for which she was exiled, arrested, and imprisoned across Europe.

Excerpted from After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz. Copyright © 2023 by Selby Wynn Schwartz. Excerpted by permission of Liveright/W.W. Norton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.