Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

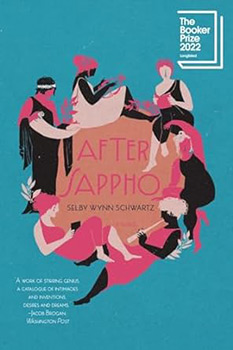

by Selby Wynn Schwartz

In 1877 she sang for her supper in a public park in Kiev, then fled the country with a false passport. Hardly had she arrived in Switzerland in search of a clandestine printing press when the police swarmed in, asking pointed questions about her revolutionary belief that women ought not be held as property.

She was expelled from France, she was arrested in Milano, she was jailed in Firenze although there was no evidence for her guilt except that she was clearly incorrigible. By 1881 she had a daughter, fathered by an Italian anarchist. Anna Kuliscioff was careful not to marry him, she had other ideas.

Dottoressa Anna Kuliscioff, 1888

Anna Kuliscioff was so often the object of outcry and imprecation that by 1884 she scarcely registered an insult. She enrolled in the university of Napoli to study medicine, despite the fact that no woman had ever done so before. She was interested in epidemiology and why on earth so many Italian women were permitted to die from puerperal fevers. At least upon her graduation in 1886, when she was decried as a pathological perversion of femininity, Anna Kuliscioff could recite the medical definition of 'pathogenesis.'

Thereafter, on the grounds of sheer human life, Anna Kuliscioff opposed the Pope, the Russian czar, and most of the Italian socialists. It was ludicrous, what these men busied themselves with instead of preventable post-partum infections. What was worse, what was truly malignant, was the casual breaking of bodies in the back rooms of a household, nearly always the bodies of women, authorized under a civil law called the patria potestas.

Patria meant both 'the father' and 'the fatherland,' and potestas was the thick knot of their power to dispose magisterially of women, children, and domestic goods. Patria potestas had been handed down from father to father since the Roman Empire. In the Pisanelli Code of 1865 it was wedded to the autorizzazione maritale, which authorized the husband to treat his wife as a child forever: no matter how she grew in mind and body, she would never be fully a person in the fatherland.

As soon as she could, Anna Kuliscioff became a doctor, specializing in gynecology and anarchism.

Amendment to the Pisanelli Code, 1877

The rights we didn't have in Italy were the same rights we hadn't had for centuries, and thus not worth enumerating. But in 1877, a modification to the Pisanelli Code allowed women to act as witnesses. Suddenly, legally, we could sign our names to what we knew to be true. Our words, which had always before been seen as gauzy and frivolous, gained a new weight as they settled on the page.

Then, too, we were beginning to notice how the outlines of our doorways and dowries were matched up, so that one box could be carried through another, signifying the transfer of a bride. No one could leave a marriage, but some of us could discern the shape that it made of our lives. As one politician said at that time, In Italy, the enslavement of women is the only regime in which men may live happily. He meant that we ourselves were the small gift, pawned for the future of the fatherland.

Excerpted from After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz. Copyright © 2023 by Selby Wynn Schwartz. Excerpted by permission of Liveright/W.W. Norton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.