Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

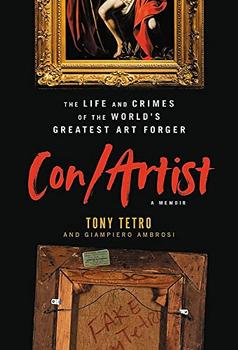

The Life and Crimes of the World's Greatest Art Forger

by Tony Tetro, Giampiero Ambrosi

My father, who thought I might be musical, bought me a guitar and arranged for me to have lessons. It was a futile waste of my time and his money. But my mother, who noticed that I had a talent for art, bought me a beginner's set of oil paints. It had little tubes of color and four or five brushes, some thinner, and a small stack of eight-by-ten canvas boards. I'd practice at the kitchen table while my mother cooked dinner nearby. When I'd get started, I'd be engrossed in what I was doing, but being only a child, my attention would start to wane after a while. Still, I was ambitious with what I painted. I tried a portrait of my dog, Duke, but I didn't yet know how to capture the way light hit the dog's hairs. My mother's friend, Mrs. Pommeroy, once complimented me, saying she thought my painting was wonderful. Instead of being proud, I said I wasn't happy at all and that I had done much better on other occasions. Even then, I was demanding of my efforts.

At Holy Family Catholic School, where I attended junior high, we were under the strict rule of grim nuns who wore full penguin habits and handed out education and their own shriveled sense of discipline—also known as corporal punishment—in equal measure. I used to draw my teacher, an old nun, as a Vargas pinup girl—long luscious legs, curvy hips, plump breasts, and a sour, wrinkled Sister Antoninus face. When she finally caught me, she smacked me hard across the knuckles with her pointer and dragged me down the hall by the ear to the principal, Father Hearn, who struggled to suppress his chuckles and made me promise to knock it off.

High school was the first time I had any real instruction in art. My teacher was a college graduate in art history who encouraged us and introduced us to the great painters and to concepts like perspective, color theory, and technique. For a lesson on abstract art, I remember I did a clumsy painting of a female nude. I got a failing grade, but nobody pulled me out of class by the ear for it. For a class on perspective, I drew a detailed view of the room, showing everything I saw in front of me. I received an A+ and was very proud. This time, I felt like I deserved it.

At night, I'd go to the public library and head downstairs past the newest class of Mouseketeers to spend hours looking at artists I had only barely heard of. I didn't understand Picasso, and Mondrian did nothing for me. I didn't get the point of mastering all that technique just to make geometric shapes with primary colors.

My teacher showed us Chagall, calling his work "visual poetry," and it was true, I could see the poetic movement of color. We were introduced to Dalí, the whole class being asked to repeat after the teacher: "Sur. Realism." Dalí was weird, but I was impressed by his imagination and thought I couldn't have come up with that kind of unusual imagery. Pointillism, to me, seemed too laborious; carefully filling in dots of color on a big canvas seemed like a waste of time. I liked the Impressionists. Their paintings were pretty and I could recognize talent in them. But to me, all of this modern art lacked soul.

What really struck a chord were the old masters and Renaissance painters. Now, my mind is trained, but then, I used to think, "How could they think up all these things—the sky, the angels, the crucifixion, the people and their expressions, the clouds, the light?" I thought it was magical that they could do that. I didn't feel that kind of awe about modern painters.

I started to learn about artists like Perugino, Verrocchio, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Botticelli, but Leonardo was the greatest hero of them all, although when I was young, I was more fascinated by Leonardo the engineer and scientist than Leonardo the artist. I was drawn to his notebooks, with their ingenious feats of engineering: his aqualung, his flying machine and parachute, the war machines, his intricate studies of human anatomy, the enigma of his mirrored handwriting. You can see how that would have captivated a boy my age.

Excerpted from Con/Artist by Tony Tetro and Giampiero Ambrosi. Copyright © 2022 by Tony Tetro and Giampiero Ambrosi. Excerpted by permission of Hachette Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.