Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

How We Live with Other Species

by Esther Woolfson

I don't remember now the first moment of realizing how much more the birds were than the very little sum of what seemed like their worryingly fragile parts, or that the rats my daughters Rebecca and Hannah kept were intelligent, complex beings but within a short time we knew that each creature possessed an indefatigable determinedness of self, a character, a place in their own world formed by geographical origin, long culture, social habits and cognitive ability. Observation told us that these creatures anticipate, enjoy, consider, grieve, love and hate. It was impossible not to appreciate that their actions were deliberate and their feelings as subtle, perceptible and as real as our own.

The timing was fortuitous – even a few years before, it would have been difficult to suggest that my family's observations had any basis in fact. The early years of our living with other species coincided with radical developments in studies of the cognitive behaviour and neuroanatomy of both humans and other species. Increasingly, news reports (many beginning with a wouldbe humorous reference to the term 'bird brains') spoke of freshly published research on the topic of avian, or other species' intelligence, and it seemed incredible only that it had taken quite so long for anyone to have noticed.

These revelations were exciting and seemed transformative. If we live in a world of sentience and consciousness, shouldn't the knowledge alter the entire basis of our relationship with other species? If these organisms are able to employ their statocysts, their chemoreceptors, mechanoreceptors, their neurons and glia, their nidopallia caudelaterale and hippocampi, their every organ and mechanism of sense, smell, direction and feeling towards living their lives much as we do ours, on what basis can we still consider ourselves superior?

The more I read and thought about what was being revealed by research and observation, the more the Scala naturae and all the ideas that surround it came to seem the shabby, selfserving and selfdestructive concepts they are. The construct appeared to represent the kind of ideas we should have examined, laughed at, and thrown away years ago, together with the anachronistic, scientifically incorrect language we still use: 'inferior', 'superior', 'higher', 'lower', 'evolved', 'less evolved', 'primitive', 'advanced'.

So extensive and damaging have been the effects humans have had on other species and on the fabric of the earth that they're described as our 'cutting down the tree of life'. Others have spoken of 'the sixth extinction' caused by massive species loss, climate change and the environmental degradation caused by human action. And yet, we still hold on to ideas of human perfectibility as if the greatest prize of all life and evolution is to be human, the endpoint of some phylogenetic metempsychosis as we jostle for the nearest place to god. I'm not 'more advanced' than my rook, my crow or the spider on the floor. As a human, I'm not even among the distinguished roll of the most successful living species. I'm simply one small part of another small part of the life of the planet. The belief that humans are not only exceptional but superior to every other species is being shown increasingly to be absurd – it seems exceptional in itself that it has taken the imminent catastrophe of species loss and global warming to begin to demonstrate what we all might have known all along, that we're only part of a chain, not the sole and brutal wielder of it.

In writing this book, I've tried to answer, not least for myself, the questions I put to the spider, questions about our shared origins, about the development of the philosophical and religious ideas that have formed our views and how we've seen, described and portrayed other species. I've asked what has allowed us to keep and kill sentient creatures in vast numbers for food, clothing, sport or entertainment. I've asked how we reconcile the sufferings of others with benefits to our own lives and health, and what kind of relationships we have with the animals we live with most closely, how we choose those to whom we will be close, those we will defend or those we won't. I've asked too what moves us to love or hate or grieve beyond the boundaries of our species, how our behaviour and attitudes towards other species is related to our behaviour towards other humans.

Excerpted from Between Light and Storm by Esther Woolfson. Copyright © 2022 by Esther Woolfson. Excerpted by permission of Pegasus Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Going Home

by Tom Lamont

Going Home is a sparkling, funny, bighearted story of family and what happens when three men take charge of a toddler following an unexpected loss.

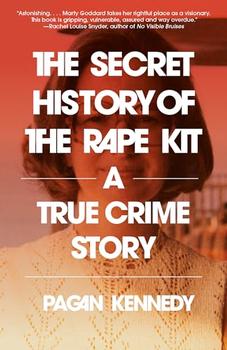

The Secret History of the Rape Kit

by Pagan Kennedy

The story of the woman who kicked off a feminist revolution in forensics, and then vanished into obscurity.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.