Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

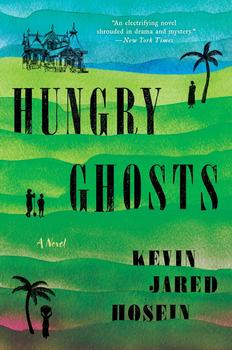

A Novel

by Kevin Jared Hosein

This, a place of lesser lives. A tangle of wood and iron that seemed to slightly shift shape every time a strong wind galloped over it. There was a communal yard for cooking and drinking and fighting. Inside, five families and five rooms, ten-by-ten-feet. Between each were cracked wooden partitions that didn't go all the way up. The cold earthen ground. Clothes stitched from old flour bags. Coconut fibre mattresses, permanently depressed, topped with pillows stuffed with sugarcane tassels. The macadam roads here had no names. Only distinguished by the frequency of their fractures.

Here, the snakes' calls blurred with the primeval hiss of wind through the plants. Picture en plein air, all shades of green soaked with vermilion and red and purple and ochre. Picture what the good people call fever grass, wild caraille, shining bush, timaries, tecomarias, bois gris, bois canot, christophene, chenet, moko, moringa, pommerac, pommecythere, barbadine, barhar. Humanity as ants on the savannah. Picture curry leaves springing into helices; mangroves cross-legged in the decanted swamp; bastions of sugarcane bowing and sprawled even and remote; the spoiled smell of sulphate of ammonia somewhere in there; pink hearts of caladium that beat and bounce between burnt thatches of bird cucumber – all lain like tufts and bristles and pelages upon the back of some buried colossus. The Churchill–Roosevelt Highway sliced that colossus in half. On one side, the belief of bush and burlap and sohari and jute and rattan and thatch and tapia. On the other was Bell Village, the dogma of a new world, howling and preaching steel and diesel and rayon and vinyl and gypsum and triple-glazed glass.

Trinidad had been killed, and now it was to be resurrected.

In Bell, the Presbyterian church stood broad as a gunslinger in a silent face-off with the temple's kaleidoscope of jhandi flags. A slow, evangelic takeover. Every week, one fewer bamboo pole and one more shilling on the offering plate, brass stained with the blood of Christ. The crucifix and the steeple so dappled in birdshit that they had merged with the mortar. The shadow of the sugar mill black like molasses. Chipped millhouses like firebombed rubble. The silos visible in the distance – tall, domed, phallic. The love children of industrialists and missionaries. England, Canada, Holland, Courland, wherever – you made sure to call them sahib or sir. Though most of them knew now that their time was almost up. Elephants marching to the graveyard.

The schoolhouse was modelled after the church.

Krishna was the only child in the barrack enrolled there. Despised it. They cut his hair. His classmates were all from Bell. Despised them all. Some were Hindu at home but Presbyterian at school. Not him. One cannot be both, is what he thought. You must choose one. Only a fool would spread his soul thin. For Christmas, the Nova Scotia missionaries and their wives brought gifts. To the boy on his right, a toy locomotive. The girl to his left, a Little Traveler's sewing kit. Her little brother, a Mother Goose colouring book and a packet of jumbo crayons. And for Krishna, a chewed pencil and a Bible, which found good use as wrapping paper for fish.

The teachers wore thick jackets in the hot sun and seemed to become aroused when they put their tamarind whips to use – each one ascribed a Biblical moniker. Gomorrah. Rapture. Revelations. A few children were whipped harder than others, Krishna among them. The boy didn't know what 'Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard' had to do with him, yet knew the first three stanzas by heart.

He had no friends at school. He was the oldest in his class because of his late start. A small group of his classmates turned the others against him when he gave the girls lice. He was pestered incessantly, the taunting maddening, like a heightening tinnitus. They spread the word that he still lived in a barrack because his grandpa loved rum more than his children. Because nobody in his family could spell their own names. Because none of them could add without using their fingers and toes. They told the class that he drank the same pondwater that the goats squatted in. That spiders nested in his food and cockroaches crawled into his nostrils at night. That he stank of his father's semen, because his father took his mother in front of him – and that he daydreamed of joining in. It was hard for him to hear those things – as some of them were true.

Excerpted from Hungry Ghosts by Kevin Jared Hosein. Copyright © 2023 by Kevin Jared Hosein. Excerpted by permission of Ecco. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Great literature cannot grow from a neglected or impoverished soil...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.