Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

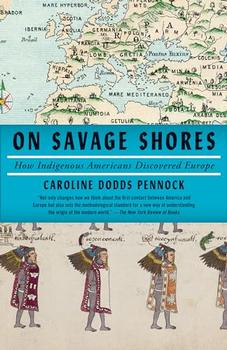

How Indigenous Americans Discovered Europe

by Caroline Dodds Pennock

When the Taínos disembarked in Palos, Columbus left two or three 'that were sick' behind and took the 'six that were healthy' on the journey to court. We know that two of the survivors were men, but no children are mentioned as arriving in Seville, so we are left wondering whether they were simply invisible to the chroniclers, or if they perished on the voyage and their bodies were tossed carelessly into the roiling ocean. The few Taínos that survived arrived in Seville, before travelling to Barcelona, where they were presented to the king and queen, along with beautiful green parrots, worked gold objects, small pearls, ornate belts, and other curiosities which 'no one had seen or heard of in Spain before'. The Indigenous people must have been a subject of incredible curiosity, for Columbus was at pains to trumpet his discovery, and people crowded the streets to look at them. We know about their arrival because Columbus's triumph is described in slightly cynical detail by Bartolomé de Las Casas—an author and friar who spent his later life campaigning for better treatment of the Indigenous peoples, who he saw as childlike innocents, in need of salvation—in his unfairly neglected and never-translated-into-English History of the Indies. Ever modest, when the newly confirmed 'Admiral' arrived at court he gave a stirring speech intended to shore up his position and secure future investments, conjuring up a picture of a land where coarse grains of gold were to be found just lying around, ready for melting. Mindful of the reputation of the 'Catholic monarchs', he also described another 'precious treasure': the multitudes of people, who were simple, meek and naked, perfectly suited to being brought to the Christian faith. At this point, Columbus ushered forward the Taíno, and Ferdinand and Isabella – inspired to help and convert these poor innocents—threw themselves on their knees, crying pious tears. The royal choir—apparently primed for this moment—then burst into song, and it seemed at that ecstatic climax that they were 'communicating with celestial deities'.

We can only imagine the Taínos' reaction to this elaborately choreographed spectacle. Ritualised weeping was not unusual among Indigenous cultures, and they were not complete strangers to the oddities of Europeans by this point, but were surely baffled by the rulers' fervent response to their arrival. Given the significant imbalance of power, it must have been quite disorientating to have the rulers kneel at their feet. The Taínos' sense of the encounter may also have been interlaced with the objects on display. Among the marvels around them were guaízas, small sculptures of faces, often made of shell. These 'faces of the living' were a symbol of kinship in Taíno culture, an embodiment of a person's spirit, often given by caciques as a way of cementing relationships. Zemís—objects connected to the life force of ancestors with complex ceremonial purposes—were also probably among the objects brought to court by Columbus. The gold figures, parrots, jewelled belts, and guaízas were gifts from Caribbean caciques, Indigenous chiefs who likely saw these symbolic exchanges as gaining some control by sacrificing part of themselves. How must the Taínos have felt, presented as objects to a foreign ruler, but surrounded by tokens of their own power? It's hard not to think these few survivors would have been despairing and overwhelmed, but what possibilities might they have seen reflected in the guaízas and other treasures, echoing the Taínos' spirits back from their surroundings?

Unlike the later Totonacs, these first travellers did not have a translator, but we know that they had quickly learned to communicate with the Spaniards 'by speech or by signs' and had been 'of much service'. According to Peter Martyr, it is due to some of these travellers that we have what may be the first Indigenous American dictionary in a Latin alphabet, for 'thanks to [them] all the words of their language have been written down with Latin characters'. Columbus himself wrote admiringly of the Taínos' swift ability to adapt, calling them 'men of very subtle wit' and, according to Oviedo, the Taíno were astute enough to go along with the situation they found themselves in. 'Of their own will and counsel, [they] asked to be baptised', a favour which was graciously granted by the Catholic monarchs who, with their eldest son John, agreed to be the godparents. Most of the Taínos were given unknown names picked by their new sponsors, but the most important men were honoured (and colonised) by being baptised 'Fernando de Aragon' (Ferdinand of Aragon) after the king and 'Juan de Castillo' (John of Castile) after his son. These two 'principal Indians' were apparently relatives of the cacique Guacanagarí, ruler of Marién on what became Hispaniola, who allowed Columbus to establish the short-lived settlement of La Navidad, the first European colony in the Americas, on his lands. The emergence of a cacique's relatives among the captives complicates our understanding of these events, as it seems less likely they were kidnapped, and they must also have joined Columbus's company after he seized the Taíno in Cuba. Were they official representatives of Guacanagarí? An eighteenth-century account, the first to be written by a Hispaniolan, says that two of Guacanagarí's sons, along with eight other indios 'of their own will wanted to go to Castile'. It is possible that the agency and engagement of the Taínos was later written into their history to create a more coherent Christian history of Hispaniola, but we also know that Guacanagarí had a strategic (if incompletely informed) attitude to his encounter with Columbus – it is not hard to imagine that he might have sent his sons as emissaries. We know that Guacanagarí himself gifted a belt and a guaíza mask to Columbus when he arrived on Hispaniola. Assuming that these objects were among those presented to the king and queen, Fernando's role becomes almost a diplomatic one: cementing the friendship secured by this exchange.

Excerpted from On Savage Shores by Caroline Dodds Pennock. Copyright © 2023 by Caroline Dodds Pennock. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.