Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

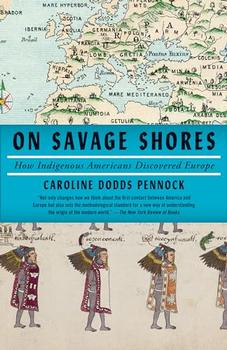

How Indigenous Americans Discovered Europe

by Caroline Dodds Pennock

Along with these two nobles, a young Taíno—who will reappear in the next chapter—was baptised 'Diego Colón' after Columbus's son, marking the beginning of a long association with the Admiral which would lead him to cross and recross the ocean. Such familial naming is a pattern which will confusingly recur in our tale; it is a form of arrogant symbolic—and sometimes literal—possession, and also shows the way in which godparentage and patronage shaped social networks and opportunities.

These forcible baptisms marked the start of five centuries of ostensibly benevolent violence against Indigenous Americans, highlighting the problematic role of Christianity in the colonial world. While friars such as Las Casas were undoubtedly involved in campaigning for legal and practical protections for Native peoples, they were also irretrievably entangled with the 'civilising mission' that led to the extermination of Indigenous cultures and beliefs, stood complicit in the 'legal' trafficking of Native peoples, and held an unwavering conviction in their own 'sacred' mission that often led them to take brutal measures in their attempts to 'save' what they saw as Christian souls heading for damnation. Columbus's 'adoption' of Diego powerfully evokes the theft of Indigenous children across the centuries: from children torn from the arms of their enslaved mothers to the 'residential schools' where Native children were ripped away from their communities and cultures, with a view to 'civilising' and 'Christianising' them. The devastating legacy of these 'schools' in the United States and Canada—revealed in excoriating detail by the 2015 report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada—has recently come to international attention, as the efforts of tribal groups to recover their ancestors have led to the discovery of the remains of thousands of Indigenous children in unmarked graves at Canadian sites alone, including Kamloops Indian Residential School, on the unceded lands of the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation.

We know that the newly baptised Fernando, along with most of the other Taínos, set sail with Columbus on his second voyage. We have no way of being sure if Guacanagarí's representatives arrived home safely—the secretary to the Venetian ambassador suggests that 'only three survived; the others died because of the change of air'—but the 'alliance' tentatively established by their gift-giving certainly had not lasted. When Columbus returned to Hispaniola he found the settlement of La Navidad razed to the ground and the crew he had abandoned there dead due to infighting and Indigenous resistance. During this period, we find plenty of what Anna Brickhouse has called 'unsettlement'—the active thwarting of European colonisation—which is often overlooked in our tendency to focus on more 'successful' settlements.

The recently baptised Juan remained in Spain as part of the royal household, for it seems that his namesake Prince John 'wanted him for himself'. Oviedo assures us that Juan was treated extremely well, taught in the ways of the faith, and given 'much love' by his royal patron. By the time Oviedo met him, Juan could speak Spanish fluently and was living as if he were the son of a leading Spanish gentleman. Two years later, he died. In common with many Indigenous voyagers, Juan's life is obscure except for these few snippets. He appears as a bit-part character in Oviedo's account of Columbus's triumphal return, and becomes an object of Spanish paternalism and curiosity, before abruptly exiting the stage. We have no way of knowing how he died, but it was probably not of old age, as an elderly person was unlikely to have been selected to adorn the royal house as a courtier and curiosity. Juan's feelings about his fate also remain obscure—he was fortunate by the standards of some of his contemporaries, but he still perished far from his home and family. Nonetheless, like many Indigenous people, it seems Juan made the best of his situation, integrating into his adopted surroundings as best he could. This deft cultural adaptation, here only obliquely glimpsed, is something we will see in the lives of many Native people as they tried to navigate the turbulent waters of early encounter.

Excerpted from On Savage Shores by Caroline Dodds Pennock. Copyright © 2023 by Caroline Dodds Pennock. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

If every country had to write a book about elephants...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.