Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

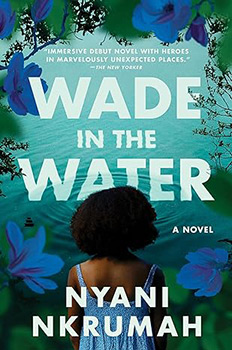

A Novel

by Nyani Nkrumah

Mr. Macabe reached and took my thumb out of my mouth and put his hand in mine. I could feel the calluses in lumps and bumps under the hardness of his palm. I could never figure out how he knew the minute my thumb was in my mouth. He had long grown tired of telling me that I was too old for that, and I'd get rabbit teeth.

"You all right, baby girl?" he asked me. "Things all right at home?"

I nodded.

"Leroy's still away?"

I hesitated, not wanting to say anything because maybe Mr. Macabe had that second sight that made him sense things no one else did, but in those seconds I waited, Mr. Macabe's voice was back again, sharper. He was now leaning forward, looking through me, trying to see deep into my soul again.

I kept it out of his reach, buried it way, way down.

"Is he back?"

"No, he's still away." I managed to keep the wobble out of my voice.

"That man's been away almost nine months this time." Mr. Macabe seemed to be talking to himself again.

He leaned back in his chair.

Leroy, my stepfather, was Ma's husband and the father of my sister and brothers. I knew he hated me. Couldn't stand to look at me.

I wanted Mr. Macabe to go right on talking about something else and not try to look into my soul, so I said quickly, "You going to be all right?"

"Yes, don't you worry that pretty head of yours over me. Just hand me a clean shirt."

I went to get Mr. Macabe a clean shirt and came back with his favorite gray shirt with the white collar.

"Want me to fix you a sandwich before I go?"

"That would be real nice. There's a piece of bacon in the fridge and some bread on the counter. Make sure you wash those grubby hands first."

I fried up the bacon and made the sandwich.

"Now, what's your new word for the day?" he asked.

"Preposterous."

"My, my, my. That's a handful for a little girl. You know what it means?"

"Yes," I said, rolling my eyes to give him some sass. "It means ridiculous, absurd, foolish, inane."

Mr. Macabe could hear that sass right in my voice, but he only shook his head and said, "You

keep it up, hear now?" He stretched out his hand, and when I grasped it, he pulled me close to him for a quick hug.

I ran down the street. Past the tiny, mostly rented clapboard houses that made up my neighborhood in the black part of town; past the big old sign where if you squinted you could just make enough sense of the peeling red paint to read "Town of Ricksville, MS, Population 8014"; past our neighborhood liquor store; past Fats's house at number 6; past Cammy's at number 8 until I reached the smallest house on Ricksville Road, number 12. It was a slightly lopsided house that you could just about tell used to be yellow. We lived in the poor, all-black neighborhood of South Ricksville, which, on our classroom map, was south of Main Street.

Years back, in 1964, Main Street and most of its stores had been burned to the ground in retaliation for what happened near Philadelphia, Mississippi, when the Ku Klux Klan had killed those young election workers turning out the black vote. All that had put in stone the open resentment between blacks and whites, and even though the white owners had rebuilt, we kids almost never ventured north of Main Street into the white part of town. Those lines, drawn in the sand between north and south, stayed unchanged over the years. Every child in Ricksville knew where they were supposed to be when the sun set. If we were sent to get something from the larger grocery five blocks into the north side, the moment the glow of the sun started to retreat, our feet had better be on North Perry. If darkness was moving in fast, we would have to run at full tilt—only when we hit South Perry could our feet slow down, and our hearts steady, and our lungs fill with air. Then we would settle into a stroll, because from there it was a straight shot from Perry to Woodlawn, Woodlawn to Grace, and Grace to Ricksville, and then we were finally home.

Excerpted from Wade in the Water by Nyani Nkrumah. Copyright © 2023 by Nyani Nkrumah. Excerpted by permission of Amistad. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.