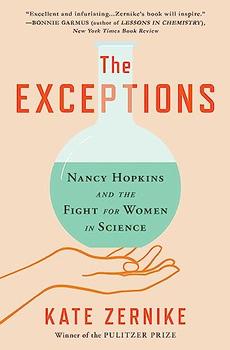

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science

by Kate Zernike

Since kindergarten she and Ann had been scholarship students at Spence, the elite girls' school on Manhattan's Upper East Side, both of them in the thick of the small class of girls in their years. Spence instilled in its girls an understanding that they were privileged, and that with privilege came responsibility. They were cultivated to do important things, to go on to Seven Sisters colleges and be the best students there, to be leaders, though leaders of a certain kind: in the Junior League, or charity work. And they should be well mannered in their pursuits: the school taught its girls never to chew gum on the bus or speak loudly in public, to defer to elders and to not boast. Arriving at school each morning, they curtsied to a uniformed doorman, which their teachers told them was good training should they ever be presented at court to the queen.

Both Nancy and Ann were known as exceptionally bright, especially Nancy. She could hear a song on the radio and immediately play it on the piano; when the woman who played at morning assembly at Spence quit, Nancy took over. She had little interest in reading, but loved math, saw a beautiful language in its order. She thought of it like eating candy: a sweet burst of pleasure in solving each problem. The telephones in their building at 106 Morningside Drive ran through a plug-in switchboard, and the operator who worked it once complained to Ann that she'd taken thirty messages from Spence girls looking for Nancy's help with the night's math homework.

Nancy's experience at Spence also taught her not to put too much value on money. Her school friends with their governesses and duplexes on Fifth Avenue wanted their playdates to be at Nancy's house, where her mother would be on the floor making papier-mâché dolls from spent light bulbs. It seemed to Nancy that her classmates' parents were out every night—she read about them in the society pages of the New York Times—and always getting divorced. She and Ann called their parents by their first names, which evolved into made-up terms of endearment, and even their classmates called Nancy's mother Budgie and her father Diegles. Proper Manhattan never strayed north of Ninety-Sixth Street, but to Nancy, her neighborhood was like a small town in the city; she and Ann trick-or-treated between apartments in their building, played on the deep sidewalk that faced Morningside Park. At Easter they went to watch the parade of hats and finery along Fifth Avenue, inventing a game to see who could pat more mink stoles. On weekends, Budgie led the family on adventures around the city: to the medieval Cloisters, or the Museum of Modern Art, where Nancy was entranced by the Kandinsky. She recalled her childhood as unusually happy, rich, not in money but in education and family.

Still, she fixated early on particular anxieties. The radio played often in the apartment, and from a young age Nancy had heard news reports about the aftermath of World War II, the emaciated and orphaned children returning home from concentration camps, a little boy who'd had his eyes poked out by Stalin's guards for the sin of putting flowers on his father's grave. How could humans act so cruelly? The Cold War air raid drills at school, sending Nancy and her classmates diving under their desks for cover, made her think these terrors could come right to her in New York City. She worried about losing her tight-knit family, couldn't imagine life if any of them died. Her father had had rheumatic fever as a child, which left him with a weak heart. When Nancy was ten, her mother had skin cancer—doctors cured it, but Nancy knew from the way her mother whispered the word that it was reason to be fearful.

Her father was quiet, New England in his ways. His grandfather had been a distinguished chief justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court and his legacy dominated the family lore. Justice Charles Cogswell Doe had been an eccentric—he kept the courtroom windows open in the winter and insisted that his four children wear only navy blue. But he had a reputation for granite integrity. From his example, which Budgie summoned regularly, Nancy understood that the worst thing you could do was tell a lie. When the calls seeking help with math homework became too frequent, she decided it would be faster if she just did the homework problems for her classmates on the chalkboard at school. When the teacher got wind of this and confronted her, Nancy replied that she had done no such thing. But she couldn't sleep that night and returned to school the next morning to confess.

Excerpted from The Exceptions by Kate Zernike. Copyright © 2023 by Kate Zernike. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

He has only half learned the art of reading who has not added to it the more refined art of skipping and skimming

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.