Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science

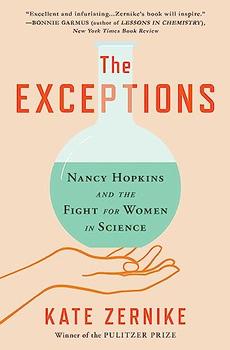

by Kate Zernike

They shared the lab room with twelve Harvard undergraduates, but still it was an unusual concentration of women. Watson created room for women partly because he liked having them around. He was looking for a wife and thought he might find one at Radcliffe. He also thought they made life more interesting. At the Nobel ceremony in December 1962 he had convinced Princess Christina of Sweden to apply to Radcliffe and, once at home, arranged with Presidents Bunting and Pusey for her to attend. (Pusey had little patience with some of the antics of his young Nobelist, but wrote back, "She sounds like a most attractive young lady and I appreciate the interest you have taken in this matter.") And Watson had an eye for talent: as his first female graduate student, he had taken on Joan Steitz, who was two years older than Nancy and would go on to be a Yale professor and one of the most highly regarded biologists of her generation. Steitz's first choice had rejected her because she was a woman: "You'll get married and you'll have kids—then what good would a PhD have done you?"

Watson wanted to fill the lab with fun people who knew when to laugh and remained upbeat even when experiments went nowhere. He liked unconventional thinkers and saw Nancy that way. He was not interested in her romantically, considered her more handsome than pretty—his taste ran more traditional and blonder. He was fascinated that she had gone to Spence, which he considered one of the nation's best schools. He was proudly Irish, from Chicago's South Side and a family richer in intellect and culture than land or cash—Orson Welles was a distant cousin, and Watson himself had been a radio "Quiz Kid" and entered the University of Chicago at sixteen. His nose was still firmly pressed against the glass. He was intrigued that Nancy's friends were debutantes from old-line families, Winthrops and Pratts. That, and her accent, which he mistook for Long Island lockjaw, made him think she was from New York society, not a building with an unfashionable address and no doorman.

The students in the lab were supposed to be doing their own experiments, but only those who had worked previous summers or semesters in labs were doing so. Nancy was still watching more than she was doing, but she was learning about science and how scientists worked. She found them open to her questions—and she had lots of them, her brain popping with ideas for experiments even if she didn't yet know how to carry them out. The pastimes that had once consumed her—Saturday excursions to Crane Beach on the North Shore, parties in Eliot House with Brooke and his roommates—no longer held her interest. Only the lab did.

Watson could be demanding and at times dismissive, turning on his heel to leave if you bored him, which Nancy tried hard not to do. He soon began ducking through his door into her small lab space more regularly with "What's new?" or "Lunch?" and calling her "kiddo." Often he would deliver a bit of information, or a joke, transmitted in his staccato: dot dot dash dot dash. He'd be gone in a flash, the door still swinging on its hinges. She'd had other instructors who related well to students—Erich Segal, who later wrote Love Story, had been among them—but Watson was unusual. She knew his extraordinary accomplishment, yet still he spoke to students on their level, griped about professors the way they did. He soon became a friend and her idol, one of the most important people in her life.

Jim, as Nancy now called him, lived in a railroad apartment in the only house on Appian Way, near Radcliffe Yard, a narrow white clapboard building where he threw crowded parties that mixed professors and students and the occasional celebrity—one party was for the princess, another for Melina Mercouri, the Greek star of the hit film Never on Sunday. If it was unusual for faculty and students to socialize like this, science was unusual, and the lab like a family, its members climbing every year onto the rhinos in front of the building for goofy group portraits. Jim's widowed father lived in an apartment downstairs. Jim doted on him—they shared a lifelong passion for bird-watching and the Democratic Party—and took him out to dinner each week. Jim began inviting Nancy and sometimes Ann, who was living in Cambridge after graduation, or their mother, who was living in New York but visited often after the death of her husband.

Excerpted from The Exceptions by Kate Zernike. Copyright © 2023 by Kate Zernike. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

There is no science without fancy and no art without fact

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.