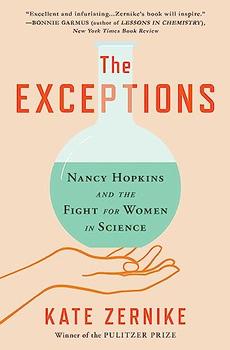

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science

by Kate Zernike

The Watsons loved to argue and talk politics, which Nancy's family had never done. It was her first stirring of a political consciousness. Jim and his father considered themselves New Deal socialists, had left the Catholic Church but kept its concern for the poor; Nancy knew only that her mother had liked FDR and that her father had been a New Hampshire Republican.

She was the happiest she had been since childhood. The lab had opened up a world she had not known existed, much less thought she might inhabit. The field was so new, the universe of molecular biologists so small, and Watson so central to it that it was all unfolding in front of her. He and his friends were still identifying the genetic code, the three-letter labels for the twenty amino acids that translate DNA to protein. They had formed what they called the RNA tie club to share notes that might advance the understanding; members were initiated with a woolen necktie embroidered with a helix and a pin with a three-letter code. Those members included some of the biggest names in science: Sydney Brenner, Edward Teller, Richard Feynman.

Every afternoon at three, students and scientists from the lab would crowd into a small square room for tea and chocolate chip cookies fetched from Savenor's by a receptionist on her old Raleigh bike. Jim had adopted the tradition from his time at the Cavendish Lab in Cambridge, England. Nancy, her fellow students, and some technicians filed in first, followed by the postdocs and then the faculty members. Jim typically entered last, silencing the room as the others waited to hear what gossip or discovery he had learned that day. The information he shared could be monumental: one day, it was that the genetic code was universal—the transfer of information from genes was the same whether the creation was a virus or a fly's wing, the leaf of a plant or the human brain.

Nancy saw how small facts from individual experiments added up to larger insights that together could answer the big questions. She began to see the elegant logic of biology; it was profound, mysterious, and yet totally sensible.

She had found her place in the world, her purpose. Bio was her "awfully interesting" thing, though she quickly concluded that Mrs. Bunting must be withholding some secret to explain how anyone with a family could also have this consuming a career. The students and postdocs worked around the clock, coming in at least six days a week and often a seventh if they needed to check a tube or skim a gel from a machine when trying to isolate a protein or a compound. Watson set the example. One Saturday night, Nancy noticed a light on under the door to his office. She pushed through to see what he was working on. He was at his desk writing what would soon become the first and classic textbook of the new field, Molecular Biology of the Gene. He looked up at Nancy, and his face told her that he did not want to be interrupted.

Nancy's roommate, Deming Pratt, saw few charms in Jim. Deming thought his gestures awkward, his clothing too baggy. He didn't even look you in the eye. Nancy was amused by his aspirations to the world of Long Island's Gold Coast and membership at the Piping Rock country club, picked up during his summer stints at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Deming, who was of that world, considered it unseemly, almost Gatsbyesque, though she did grant Jim's request to attend her twenty-first birthday at her family's estate. (There she noted that he couldn't waltz.)

Nancy's boyfriend, Brooke Hopkins, sometimes joined her outings with Jim, but professed little interest in her new world. Brooke and Nancy had met at a freshman mixer her first week, and he was the kind of boyfriend she had dreamed of in girls' school, where her classmates had convinced her that good grades would scare boys away. Six foot five, a rower with dark reddish hair and brown eyes, he came from a conservative Social Register family in Baltimore, had gone to Hotchkiss and gotten into Harvard on mediocre grades and, he presumed, family legacy. He was doing his best to rebel, listening to jazz and reading Freud and James Baldwin. He had been recruited by the Porcellian Club, the most elite of Harvard's all-male social clubs and the proving ground for the future leaders of American social, political, and business institutions, who, it was understood, were almost always white and rarely Jewish. He'd joined Fly Club instead, thinking it more progressive.

Excerpted from The Exceptions by Kate Zernike. Copyright © 2023 by Kate Zernike. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Happiness belongs to the self sufficient

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.