Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

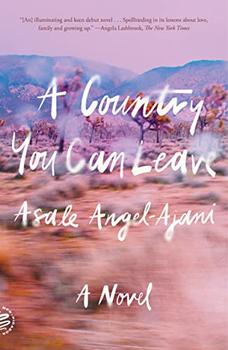

A Novel

by Asale Angel-Ajani

"Don't Minnie look silly?" says an older white woman. She's standing in the carport on a step stool, attaching a rainbow umbrella hat over a yellow baseball cap worn by a second, taller old woman. They wave at Papa Bear.

Papa Bear smiles at them, polite and exaggerated. To me he says, "She's Mickey and the other is Minnie. Get it?"

"Yeah." I don't get it, but I know it's easier to just go along.

"Their names. Their actual names." He's shaking his head, as if he's looking at the eighth wonder.

I grunt a false half laugh, not confused by their names but by the winter clothes they're wearing. Shapeless jeans and baggy sweatshirts, and neither of them is sweating.

Several trailers down we stop next to a cramped front porch with steep carpeted steps. It looks the same as all the others except in the covered carport there are black plastic garbage bags flung one on top of the other like bodies in an open grave.

"Don't mind that crap," Papa Bear says, his eyes on the swell of my mother's breasts. "They'll come 'round to collect in a day or two."

My mother considers the place, shaking her head. Fishing her cigarettes out of her fake Chanel, she lights up carefully. Yevgenia always takes her time before haggling over the rent. It's her game. Acting as though she's deliberating from a long list of nonexistent options. She sighs, annoyed, glancing at the mess in the carport, pretending those bags interrupt some big plan of hers. Amid the dilapidations and failures, my mother, Yevgenia, a woman who accidentally defected from the Soviet Union in the 1980s, is at her most Russian. She will make anything work. A broken washing machine, a flat tire, a foreign country. This.

I don't want to be here but it's not like I'm at risk of running away. Though my mother wouldn't care. The truth is, she's tethered to me by weak strings of obligation. Nathaniel "Nate" Basmadjian taught me this, and how to scrunch my body into a tiny ball on the floor of the car, while he and my mother drove around town. One night, Nate hinted that if my mother "lost the Black kid," he'd marry her and within a few days, they were off. I was five at the time so the recollection is vague. What I do remember of my life without Yevgenia is time spent with the strange people my mother pawned me off on. The Polish Seventh-day Adventist couple who liked to show me pictures from their missionary trip to Botswana, saying, "This is your culture, dear," until I nodded my head like I understood. The pretty Canadian coke addict who made me lie on the floor at the foot of her bed while she talked to me about her married boyfriend until I fell asleep. Then there was the large family from Guam who worked me like a slave and called me nekglo ñamu, black mosquito, in their Chamorro language, which was "amazing that they even knew those words," the eleven-year-old cousin told me, since the U.S. burned all the dictionaries in his country.

So not exactly foster care, but something like it.

Acquaintances from Yevgenia's various jobs. People who owed her a favor. She exhausted everyone with promises she would send more money, be back soon. She was gone for nearly two years. Supposedly embarking on a new life in Scottsdale as a blonde named "Evie" who played mixed doubles every Saturday. When my mother returned to me in California with brown roots and an allergy to shrimp cocktail, she didn't speak too much about tennis or Nate or Arizona, so I didn't ask.

Those years without her created a savage hunger in me that's hard to shake. When I was eight, nine, and ten, Yevgenia had to cleave me from her body whenever she left for work or to go to the store. At twelve, thirteen, and fourteen, I yoked my mother, leaving little space between us as she sat to read, on the sofa or in a chair. If she closed a door, my back would be pressed against it. I was the inextricable daughter, physically and mentally. But now, as we arrive at the Oasis during this Indian summer, as I enter what will be the merciless year of sixteen, I am ready for the grip of longing to finally loosen. And there's relief, like letting go of a sweaty hand.

* * *

THE DESERT HEAT is powerful, an unrelenting foe of the living. Papa Bear and my mother seem unfazed by it. I wipe my brow with the back of my hand, my eyes on the cigarette strangled between Yevgenia's two fingers. She sucks smoke deep into her lungs, frowning. Papa Bear is not looking at her face so he can't see her dissatisfaction. Yevgenia clears her throat, loudly. She motions her cigarette in the direction of the piles of trash in the carport; he jerks his eyes away from her chest, nervous.

Excerpted from A Country You Can Leave by Asale Angel-Ajani. Copyright © 2023 by Asale Angel-Ajani. Excerpted by permission of MCD. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.