Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

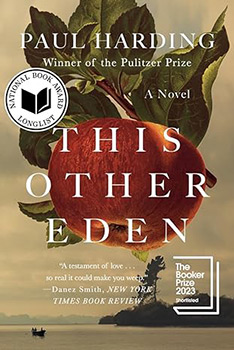

by Paul Harding

Esther drowsed with her granddaughter, Charlotte, in her lap, curled up against her spare body, wrapped in a pane of Hudson's Bay wool from a blanket long ago cut into quarters and shared among her freezing ancestors and a century-old quilt stitched from tatters even older. The girl took little warmth from her rawboned grandmother and the old woman practically had no need for the heat her grandchild gave, no place, practically, to fit it, being so slight, and so long accustomed to the minimum warmth necessary for a body to keep living, but each was still comforted by the other.

Esther's son, Eha—Charlotte's father—rose from his stool and one at a time tossed four of the last dozen wooden shingles onto the embers in the stove. The relief society inexplicably had sent a pallet of the shingles to the settlement last summer. There was no need for them. Eha and Zachary Hand to God Proverbs were excellent carpenters and could make far finer cedar shingles than these. But as with each of the past four years, summer brought food and goods from the relief society, and some of the supplies were puzzling to the Apple Islanders, like the shingles, orva horse saddle, once, for an island that only had a handful of humans and three dogs on it. With the food and stock also came Matthew Diamond, a single, retired schoolteacher who under the sponsorship of the Enon College of Theology and Mission traveled from somewhere in Massachusetts each June to stay in his summer home—visible on the mainland in clear weather 300 yards across the channel, in the village of Foxden— and row his boat to Apple Island each morning, where he preached, helped with a kitchen garden here, a leaky roof there, and taught lessons in the one-room schoolhouse he and Eha Honey and Zachary Hand to God Proverbs had built.

Useless spalt anyway, Eha said, closing the woodstove on the last of the shingles.

Tabitha Honey, Eha's other daughter, ten years old, two years older than her sister Charlotte, scooted on her behind across the cold floor to get closer to the stove. She wore two pairs of stockings, three old dresses, a donated wool coat the society had sent, and the one pair of shoes she owned, boy's boots passed down from her big brother, Ethan, when he'd outgrown them. They were too big for her and she'd stuffed the toes and heels with dry grass that poked out of the split soles like whiskers. Tabitha wore another square of the Hudson's Bay blanket wrapped over her head and shoulders.

C'mere, Victor, Tabitha said to the cat curled behind the stove. Tch, tch, c'mere, Vic. She wanted the cat for her lap, for some warmth. Victor raised his head and looked at the girl. He lowered his head back down and half-closed his eyes.

I hope you catch fire, you no-good hunks, Tabitha said.

Ethan Honey, fifteen, Eha's oldest child, sat on a wooden crate across the room, in the coldest corner, drawing his grandmother and little sister with a lump of charcoal on an old copy of the local newspaper that Matthew Diamond had given him last fall the day before he closed up his summer house and returned to Massachusetts. The boy's nose was this other red, his lips purple. His fingers and hands were mottled white and blue, as if the blood were wicking into clots of frost under their skin. He concentrated on his grandmother and sister and their entwined figures came into finer and finer view across the front page of the Foxden Journal, seeming to hover above the articles about the tenth annual drill and ball, six Chinamen deported, a missing three-masted schooner, ads for fig syrups, foundries, soft hats, and black dress goods.

Tell us about the flood, Grammy, Tabitha said, still eyeing the cat.

Charlotte lifted her head from her grandmother's breast and said, Yes, tell us again, Gram!

Ethan looked from his drawing to his grandmother and sister and back. He said nothing but wanted as much as his sisters for his grandmother to tell the story about the hurricane that had nearly sunk the island and had nearly swept away his whole family.

Excerpted from This Other Eden by Paul Harding. Copyright © 2023 by Paul Harding. Excerpted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.