Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

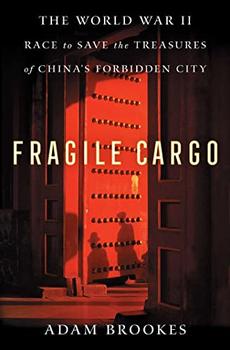

The World War II Race to Save the Treasures of China's Forbidden City

by Adam Brookes

At 5 a.m. Qianlong takes a drink of sweetened swallows' nest soup. The eunuchs bear him out of the Forbidden City through a western gate to the Lake Palaces. At six he breakfasts in the Studio of Convivial Delight, the dishes—meats, dumplings, soups—prepared in a kitchen with a hundred stoves and brought to the table in wrappings of yellow silk. The setting for the emperor's breakfast is magnificent. He eats from dishes of silver, and from porcelain manufactured in the imperial kilns, with implements of silver, gold, and jade. He eats alone, and quickly. After fifteen minutes he is gone, his leavings distributed among his family and household.

As dawn breaks, the litter brings Qianlong back into the Forbidden City, to his study in the Palace of Heavenly Purity, where, surrounded by books and maps and paintings, he passes some time reading. He reads, in classical Chinese, from texts on history and government, immersing himself in the precedents set by his forefathers, learning from their reigns. The emperor has many faces, and he must be master of them all. To his Manchu-dominated court and military, he is the scion of a conquering dynasty. To the Chinese-speaking bureaucracy and elites, and hundreds of millions of his subjects, he is a ruler in the Confucian tradition of ethics, statesmanship, and ritual, a bringer of moral order, stability, and prosperity. To Tibetans and Mongolians, he is a devout Buddhist, studying the scriptures and worshipping at the shrines of the Buddha and the bodhisattvas. Qianlong is divine ruler, soldier, scholar, and arbiter of tradition and culture for the entirety of the diverse, polyglot Qing empire.

Between 8 and 10 a.m. the emperor changes his clothes and sits with some of his favorite courtiers drinking tea and composing poetry. At ten he returns to his office at the Hall of Mental Cultivation, and the day's work begins. He reads reports from all corners of the Qing empire, responding to them with brush and ink in his clear, fluid calligraphy. He receives officials to discuss matters of governance and appointments to bureaucratic positions. At around 3 p.m. he is served another meal and naps for a while. At 4 p.m. he eats pastries with Fuheng, a trusted military commander. Perhaps they discuss their plans for the campaign in the south against the Burmese that is to begin later in the year.

By 5 p.m. the day's business is done. The emperor withdraws into the Room of the Three Rarities, a small, cozy study near his sleeping quarters, where he sits cross-legged on a warm kang. The room is named for three exquisite works of calligraphy that Qianlong has installed there, and it is where the emperor indulges in one of his greatest pleasures, viewing the art and antiquities of the imperial collections.

On this day he passes two hours in the company not of courtiers or consorts but of objects, handling them, holding them, considering them. Sometimes he impresses his seal upon a painting or composes a poem inspired by a bronze or a piece of porcelain. We do not know exactly which pieces he views on January 28, 1765, but in the days around this date he views a painting called The Stag Hunt, attributed at the time to an artist working in the tenth century ce. The painting depicts a lean, vigorous huntsman, perhaps of the Mongolian steppe, astride a furious, charging horse. Bow in hand, the huntsman leans over the horse's neck, oblivious to everything but the chase. A wounded stag lies prostrate, in its death throes. The painting is a startling study of motion and balance, violence and pain. Qianlong, deeply impressed by the work, imprints his scarlet seal upon The Stag Hunt and writes a poem in its praise. Around this time he views and affixes his seals to landscapes by masters whose work dates from the fourteenth century. He composes poems extolling an ancient ritual axe in jade, and a beautiful jade bowl, and delicate porcelain. Qianlong is liberal with his poetry and with his seal; some of the greatest masterpieces of China's art are festooned with his mark.

Excerpted from Fragile Cargo by Adam Brookes. Copyright © 2023 by Adam Brookes. Excerpted by permission of Atria Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A few books well chosen, and well made use of, will be more profitable than a great confused Alexandrian library.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.