Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

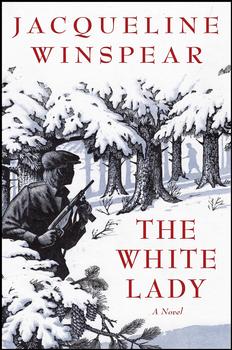

A Novel

by Jacqueline Winspear

"Chameleon," said Rose.

"What, love?"

"The lizard you were talking about—it's called a chameleon."

As time went on, Rose thought the woman was more like a hermit crab, one that Susie had tempted away from its shell house. It seemed the White lady smiled a little more with each encounter, and sometimes even waved when their paths crossed as Rose and Susie were on their way to the farmhouse. She often stopped to talk now, just a few words here and there, though Susie remained the focus of her attention. It occurred to Rose that the woman might have trouble making friends—perhaps she never knew quite what to say. Some people were like that. "Fumblers," her aunt had called them: people who weren't very good at having a chat or passing the time of day with a neighbor. Perhaps Miss White was one of those—more at ease in the company of children, though it had taken a while. Or she could have been widowed and lost a child, because there was a sort of melancholy about her. Rose couldn't help speculating—after all, she was an orphan on account of the war, so anything was possible, and she knew what it was like to lose people you loved.

Rose considered inviting the woman in for a cup of tea, now that they were on friendlier terms. She said as much to Mrs. Wicks, who frowned and tutted, then counseled that it was never a good idea to get too familiar with your betters. They might seem gracious enough, but they were all the same, those sort of people—nice to your face, but the bonds of fellowship were limited to their equals. Rose agreed that Mrs. Wicks probably knew best, but she still thought it would be a good idea, one day, because that White lady seemed a very nice person. And after all, she might be lonely, on her own in that grace-and-favor house along the road. She had probably been used to having lots of people around her when she worked for the king and queen or the government. Indeed, the image of a hermit crab was uppermost in Rose's mind; she remembered learning that they were quite social creatures, down there on the sea bed, though they scurried back to their shelters on account of their outsides being quite fragile. They had to protect their insides, those hermit crabs. Rose had liked nature study—it was her favorite subject when she was a girl in school. That's how she knew about chameleons.

Elinor White stood at her kitchen sink and stared out of the window, across fields where in the distance cattle grazed, flanked by lush woodland. If she turned and walked through the house to the front door, she would view another part of the garden, one that a passing rambler might stop to admire—a very traditional English garden, with a poetic blooming of narcissus, daisies and foxgloves bordered by a goodly planting of heritage roses. The narrow country road was just beyond her white picket fence. The opposite side of the thoroughfare formed the eastern perimeter of Denbury Forest, a mixed woodland of conifer and deciduous trees that extended for miles, dissected by a branch of the South Eastern railway and dotted with farms and cottages.

Elinor's back garden was devoted to the practical, to the growing of vegetables, the mulching of compost and a trellis bearing honeysuckle, chosen with care to provide pollen for the farmer's bees working away in hives on the other side of the fence. Her father had kept bees when she was a child, in Belgium, so nurturing something that gave such sweetness was a thread stretching down through her past. She enjoyed this benign memory; there were other strands of reflection reaching back over the years that were akin to electric cables, able to shock if touched. Those hot wires of remembrance were all around her.

She took up a pair of binoculars and held them to her eyes, scanning the landscape from her window. Dozens of crows, sparrows, blackbirds and starlings swooped down to follow a farmer's plough as it moved across a field, the horses pulling hard, finding balance in the rich clay soil. It was the only sign of life she could ascertain beyond the house, so she put the binoculars aside, pulled on a pair of leather work gloves, and set off into the garden, having pushed her feet into a pair of black rubber boots.

Excerpted from The White Lady by Jacqueline Winspear. Copyright © 2023 by Jacqueline Winspear. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.