Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

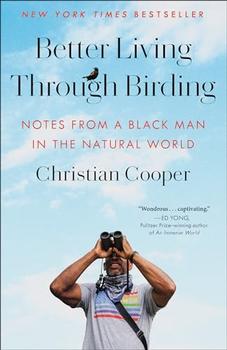

Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World

by Christian Cooper1

An Incident in Central Park

I am a Black man running through New York's Central Park. This is no leisure run. I'm not pushing for a new personal best, though my legs pump in furious rhythm. I'm running as if my life depends on it. And though my heart pounds, it's as much out of mounting panic as it is cardiovascular stress. I know what this looks like. My sneakers are old and muddy, my jeans in need of a good washing, and my shirt, though collared, could at best be described as unkempt. I am a Black man on the run. And I have binoculars.

This is not how this evening was supposed to unfold. But all it took was a brief exchange of words to put me in flight. Twilight is racing along the horizon, and I've got half an hour of light left at best. As the sun sinks behind trees wreathed in its glow, so, too, does a feeling of desperation in the pit of my stomach. I'm running out of time.

I check the alert on my phone again and curse myself for turning it off for the entire workday. I'd faced several grueling tasks with hard deadlines and had found the constant vibrating notifications from the Manhattan Rare Bird Alert too indiscriminate ("rare" being rather loosely defined by some contributors) and too distracting during working hours. I preferred to do my birding early in the morning anyway. Then I would head directly to the office, where my colleagues have grown accustomed to my business-questionable attire this time of year (functional and subject to deferred laundering; the demands of my spring migration schedule don't permit much else). So it wasn't until 6:00 p.m. that I turned my phone on and saw the text from Morgan:

"Are you going to go see the Kirtland's Warbler?"

Amusement at what obviously had to be a prank quickly morphed into disbelief as I read the chain of alerts that had preceded it. "Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God!" I sputtered, snatching the binoculars off my desk and hurtling out of the office without explanation. At least one co-worker would tell me later that he was certain someone had died.

Now, having sprinted from my office in midtown to the west side of the park near the Reservoir, I slow as I near where I think I need to be. After a few minutes a sinking feeling settles in that I must be in the wrong spot. But as I round a bend in the path, I see a mass of people—nearly all of whom I recognize—and know I've found the place.

Birding Tip

The fastest way to find a widely reported rarity is to look not for the bird but for the coagulation of birders already looking at it.

Reading my stricken expression and ragged gasps as the cocktail of panic and exertion that they are, Mike peels off from the crowd and intercepts me. "Breathe," he says, calm, compact, and dryly British as always. "It's still here; we're looking at it right now." And with a little help from my friends, I find the right spot in the right tree; lock onto the motion among the leaves; and raise my binoculars with hands shaking with anticipation. A bird, slate blue and yellow and smaller than a sparrow, moves from branch to branch with a pump of its tail. I see a unicorn, come alive before my own eyes.

In order to truly appreciate that moment, you must first understand something about this particular bird. The rarest songbird in North America, Kirtland's Warbler is a creature even more unlikely to be spotted in Central Park than the gay Black nerd with binoculars looking up at it. It nests strictly in jack pines of a certain age, habitat requirements so specific that in all the world there are only about six thousand of the birds, restricted to a breeding range that consists almost entirely of a small patch of Michigan. Kirtland's Warblers return there every spring from their wintering grounds in the Bahamas, traveling hundreds of miles to do so. Yet in that routine annual journey, one of these tiny bundles of feathers happened to wander a bit off course, or maybe, like me, this rare bird yearned to taste life in the big city, where freaks of nature of every kind are welcome. It would end up somewhere in the eight hundred acres of Central Park, a tiny thing flitting behind the leaves of the park's eighteen thousand trees teeming with a million or so other avian visitors, including other warblers from which, to the untrained eye, a Kirtland's is indistinguishable. In the words of Captain James T. Kirk, "Finding a needle in a haystack would be child's play by comparison."

Excerpted from Better Living Through Birding by Tom Cooper. Copyright © 2023 by Tom Cooper. Excerpted by permission of Random House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A book is one of the most patient of all man's inventions.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.