Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World

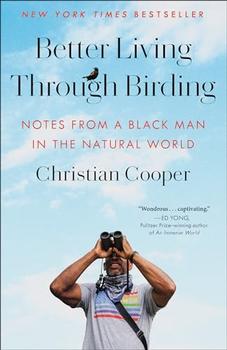

by Christian Cooper

Enter the birder Kevin Topping. He happened to be at the right place at the right time, but though luck plays a part in any sighting, there's so much more to getting the bird than that. A birder is alert to the presence of creatures that "civilians" would likely never even notice; they'd just walk right past. A birder's eyes lock onto a particular kind of motion in the trees, distinct from that of leaf movement in the wind, or to a particular shape that, motionless, is meant to camouflage into its surroundings. And a birder's ears never turn off, akin to a police scanner that snaps the attention into focus and sends one springing into action when, from amid the constant chatter, an urgent message (a distinctive bird vocalization) comes through. Then there's the accumulated knowledge base that an experienced birder brings to bear—a familiarity with what to watch for in what habitats, and an almost intuitive grasp of the subtle details of behavior, of plumage, that let you sort one kind of bird from another. Kevin Topping not only had the skill to find the bird but knew enough to know what he was looking at, and he had the presence of mind to get the word out to the broader birding community in a timely fashion.

That's how, for the first time in history, a Kirtland's Warbler was recorded in Central Park. It's as if you stepped into your backyard and saw a wild tiger prowling your lawn, or as if you looked over the side of a boat to catch a wink and smile from a mermaid before she dove beneath the waves. Or as if a real live unicorn stepped out of the forest.

This, then, is the seventh of the Seven Pleasures of Birding, and perhaps the greatest thrill of the pastime:

Seventh Pleasure of Birding: The Unicorn Effect

It's the thrill of seeing at last for oneself a creature that until then has existed only in the imagination. But while number 7 is the high-octane moment, other pleasures make birding a joy for almost anyone, as I have tried to tell my feckless friends; they wonder why I abandon them every year in May, the peak of Central Park's spring songbird migration, when I become an early-rising, sleep-deprived mess of a man instead of carousing with them. After one too many attempts to explain, I codified those aspects of the birding experience into the Seven Pleasures of Birding, for ease of dissemination to the uninitiated, and of those seven pleasures, this comes first and foremost:

First Pleasure of Birding: The Beauty of the Birds

If you've never seen a male Scarlet Tanager in full breeding plumage—a bird of such incandescent hue, set off by jet-black wings and tail, that it makes a stoplight look dim—then a knock-your-socks-off experience awaits you. And that's just the beginning of the show, from the gaudy, Technicolor riot of a Painted Bunting to the serene, pristine grace of a Great Egret; from the effortlessly soaring majesty of a Golden Eagle to the fierce frenzy of a hummingbird; from the bold color blocks of a Red-Headed Woodpecker to the exquisite nuance of pattern and muted tones of a Lincoln's Sparrow...

But most people don't realize the reasons why, of all the spectacular creatures with which we share this planet, birds captivate us as no others can.

What makes birding such a phenomenon? Why not "mammaling" or "insecting"? Certainly those pursuits have their adherents, as the thousands who visit Africa on safari or who catalog butterflies can attest. And in fact, there's a large degree of overlap among all these obsessions, counting myself as one of the multi-obsessed; once you tune in to one aspect of nature, you eventually become aware of the whole connected network of life around us.

Birding, however, occupies a sweet spot of accessibility: The variety of birds, no matter where you are around the globe or what kind of place you're in—city, suburb, country; mountains, woodland, field, swamp, shore, or out to sea—greatly exceeds the limited number of species of mammals in the same area; and many of those mammals are nocturnal and/or hidden beneath the soil or under the sea, restricting observation. Bugs, on the other hand, present the opposite problem: The crazy profusion of insect species is nigh impossible to master, or else, in temperate climes in the wintertime, there are almost none at all. With birds, no matter the time of year, there's always something to see.

Excerpted from Better Living Through Birding by Tom Cooper. Copyright © 2023 by Tom Cooper. Excerpted by permission of Random House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.