Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

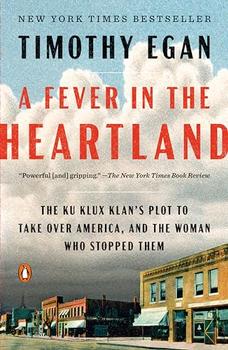

The Ku Klux Klan's Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them

by Timothy Egan

When the South refused to grant basic rights to the formerly enslaved, the region was put under military control and divided into five districts. Reconstruction of a new society was mandated by Congress and enforced by federal troops. Defiant local governments were replaced by law-abiding ones. But now the Klan had a larger purpose: it turned to terror. The silly rituals and silly titles gave way to insurrection. In Tennessee, they started raiding at night, destroying property, breaking into homes, firing shots. Black people who promoted voting were lashed and burned. White teachers in Black schools were dragged from their homes and ordered to leave. One was pistol-whipped and told that "no damn Yankee bitch should live in this county." In Mississippi, the Klan drove out nearly every teacher in a Black school. At the same time, independent Klan units sprouted in California, where migrants from China were nearly 10 percent of the population. Arsonists burned a Methodist church that had housed a Sunday school for Chinese children. The Klan in San Jose issued a threat to farmers in the southern Bay Area: they would destroy all crops of people who hired a single Asian.

Throughout the South and parts of the West Coast, young Klansmen acted with impunity. Their pamphlets were bold and declarative of their purpose, as one proclaimed: "Unholy blacks, cursed by God, take warning and fly." With confidence came arrogance. By 1868, Forrest boasted of a tide of newborn rebels—40,000 Klansmen in Tennessee, a half million throughout the South, in every province of the former Confederacy. "It's a protective, political, military organization," Forrest told a reporter. When this interview was reprinted in papers around the nation, people were shocked. The North had won the war. The South was winning the peace. And when asked about this assertion, Forrest did not deny it. "If they send the black men to hunt those Confederate soldiers whom they call Kuklux, then I say to you, 'Go out and shoot the Radicals.'"

In July 1866, a white mob backed by police stormed a Black political gathering in New Orleans, stomping men to death, shooting, stabbing, and mutilating others. More than thirty people died and 160 were seriously hurt before federal troops restored order. A similar scene bloodied the streets of Memphis that year—a three-day war that killed forty-six Black people and reduced twelve schools and four churches to ash-heaps. In Arkansas, more than 2,000 African Americans were murdered in the months leading up to the 1868 presidential election. In Lafayette County, Mississippi, thirty Black residents were driven out of their homes and forced to the water's edge, where they were drowned. In the years that followed, people who fished the Yocona River snagged human skulls and bones from the depths.

"The Freedmen are shot and Union men are persecuted if they have the temerity to express their opinion," said General Philip H. Sheridan, whose military district included Louisiana and Texas. A Tennessee authority complained to President Johnson that the Klan rode freely at night, "causing dismay & terror to all—Our civil authorities are powerless."

Johnson was frequently drunk and openly foul-mouthed, a quarrelsome Tennessee Democrat put on the ticket in 1864 by Lincoln as a unity gesture. Just days before he was murdered, Lincoln had become the first president to publicly raise the prospect of full African American citizenship. Johnson, sworn in six weeks after Lincoln began his second term, would have none of his predecessor's vision. He ignored pleas from civil authorities to go after the Klan, and he urged Southern politicians to balk at expanding the Constitution. "Everyone would and must admit that the white race was superior to the Black," he said. He vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, a legislative attempt to extend real power to the formerly enslaved, but was overridden by a strong majority in Congress. "This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am president, it shall be a government for white men," he wrote that year. He then announced an amnesty proclamation for ex-Confederates, an unconditional pardon, restoring all rights except property ownership of human beings.

Excerpted from A Fever in the Heartland by Timothy Egan. Copyright © 2023 by Timothy Egan. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The silence between the notes is as important as the notes themselves.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.