Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

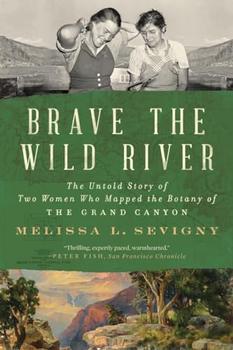

The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon

by Melissa L. SevignyPrologue

Stranded

The night was full of noises. The driftwood campfire snapped and spluttered, casting a circle of light on the river-rippled sand. Beyond, darkness pressed. Somewhere in the undergrowth a small creature rustled and scratched. The willows fringing the sandbar made a susurration as water rushed round their roots. Over, under, through it all, ran the Colorado River.

It was nothing like the sultry summer nights she had spent as a girl in Michigan, with a chorus of crickets and a percussion section of frogs. Michigan was a world of water, hemmed by lakes and stitched with rivers. Here, in the wilds of Utah, stone and sky prevailed. The high faces of the canyon walls boxed her in. The river, sloshing the shore, resounded as loud as an ocean.

Lois Jotter was alone. She shouldn't have been there—that's what people would say. Certainly not separated from her companions in the depths of Cataract Canyon, the place everyone called "the graveyard of the Colorado River." The date was June 23, 1938. At the age of twenty-four, she had come, with her mentor and colleague Elzada Clover, to collect plants. The two women, both botanists from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, had set off down the Green River in Utah with four companions and three boats. They intended to raft more than 600 miles down the Green and Colorado rivers to Lake Mead, passing through the Grand Canyon along the way.

From above—though it would be decades, yet, before satellites and space travel would show the world this way—the Colorado River's watershed looks like a ragged, many-veined leaf, its stem planted firmly in the Gulf of California. In a wetter climate it might be invisible, hidden by the canopies of trees and overhanging banks of flowers and ferns. But here, in the American Southwest, the river carves and folds the landscape around it as if water holds a weight not measured in ounces. Its headwaters begin in the Wind River Range of Wyoming, a jumbled stretch of the Rocky Mountains, where cold rivulets of snowmelt wake beneath ice each spring to surge into a thunderous rush and pour into the Green River. Jotter and her companions had floated a placid stretch of the Green, 120 miles through the red rock of Utah, where the river loops and doubles back like a dawdling tourist in no hurry to reach the next vista.

Earlier that day, they had reached the confluence where the Green joined another tributary known, until not long before, as the Grand. It, too, draws its headwaters from Rocky Mountains west of the Continental Divide. The Grand was shorter than the Green, but it had won the affections of a Colorado congressman named Edward Taylor. In 1921 he successfully lobbied to rename the smaller tributary after its main channel: the Colorado River. "The Grand is the father and the Green the mother, and Colorado wants the name to follow the father," Taylor said in his persuasive speech to the U.S. House of Representatives, adding as further evidence that the Grand was a much more treacherous river than the Green, killing anyone who tried to raft it.

Downstream from Jotter's campsite, the Colorado River swept on into deepening canyons, one after the other—through Cataract, Glen, and the Grand Canyon, 277 miles long and so deep it exposed the raw bedrock of the world. The Grand Canyon ends near the border of Arizona and the tip of Nevada, where the still-filling reservoir of Lake Mead behind Boulder Dam (now called Hoover Dam) momentarily knotted the river into a lake. Routed ignominiously through hydroelectric turbines, the Colorado then meanders southward, unraveling into a ribbon on the border between Arizona and California. It gathers one more major tributary along the way, the Gila River, before losing itself in the delta in Sonora and Baja California, Mexico.

The river was an attraction for a botanist, particularly one interested in thorny things. No one had ever formally surveyed the plant life of the Colorado River through the canyonlands, considered by some the most mysterious corner remaining in the United States. Tucked into side canyons, braving what Jotter called "barren and hellish" conditions, were tough, fierce, spiny cacti no one had ever catalogued. This was why they had come: to "botanize" the canyons and discover the plants that thrived in secret nooks and crannies up and down the Colorado's sheer cliffs and shifting sandbars. If they succeeded, Jotter and Clover would bring out a trove of pressed plants for scientific research. The plants would be an essential record of a region that was changing fast. Once filled, Lake Mead would become the largest human-made reservoir in the world; exotic plants and animals had been accidentally or deliberately introduced into the river channel; and more tourists arrived by the day. Jotter and Clover had the chance to do what no one had done before: chronicle those changes through a botanist's eyes.

Excerpted from Brave the Wild River by Melissa L. Sevigny. Copyright © 2023 by Melissa L. Sevigny. Excerpted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Discovery consists of seeing what everybody has seen and thinking what nobody has thought.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.